Reunions

| Dachau | CMOH | Reunions | E-Mails | Memoirs |

|

157th

Regimental Reunion at Gettysburg, PA Our drive from Cary, NC to Gettysburg, PA, courtesy of my son Albert P. Panebianco and daughter, Michele MacDade, was pleasant and enjoyable. We could not have made the trip without them. The trip was 350 miles and took six hours. Upon reaching our destination, Country Inn and Suites by Carlson, the first person I saw was my good friend, LTC, Hugh F. Foster III (Ret.) who was responsible for the arrangements of this reunion. Hugh is our Recording Secretary, Historian and Author. After my absence of nine years from reunions, due to illnesses, we hugged and were so very happy to see each other. This was one of the best reunions I attended. The hotel was the greatest and they could not do enough for us. After checking in, we went down to the hospitality room and what a reception we received. My son Al P., daughter Michele, Tina and I were very much surprised. This group was the kindest and most considerate I have ever met. They really made us feel welcome. The room was well supplied with hoagies , beverages and assorted snacks. The following day we visited the National Park Visitor Center (movie, museum, cyclorama and lunch). The movie and cyclorama impressed everyone. The sound and pictures were excellent. After touring the visitor center, we boarded busses for the battlefield tour. One would have to spend a day to read all the memorials. The next day, we visited the Eisenhower Farm. His home is beautiful and the surrounding land is conducive for relaxation. Farming and cattle raising is still very active on the land by nearby farmers. What a place to relax and just think. On our last day, we had our Memorial Service, business meeting and banquet. During the past year, 21 veterans of the 157 passed on. At our meeting, it was decided we will continue on with our reunions and our next one, 2010, will be held in Asheville, NC. It is one of the most beautiful spots in the country. We had the most delicious banquet dinner at the Dobbins House. Looked like most of our group could not finish their meal. There was just too much food on their plate. I was very happy to see Major Robert Foster, Hugh’s son. I last saw him in Reipertswiller, France 1989 when he was about age 12. Since that time he has graduated from West Point, spent some time in Iraq, was seriously wounded and returned to the U.S. He is now married to Carolyn and they have been blessed with a handsome son, Kevin. I want to personally thank Hugh for taking me to St. Francis Xavier Church on Sunday and then returned to pick me up after Mass. I might add, this church building was used to house wounded soldiers of the Civil War. I want to thank Betsy and Jay Wright for all their help. Being confined to a wheel chair, these people made this reunion a most enjoyable one for me. Our hospitality room was enjoyed by everyone. A great time was had by all. Until we meet again, best wishes for a healthy and enjoyable year. Albert R. Panebianco

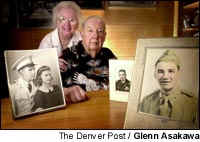

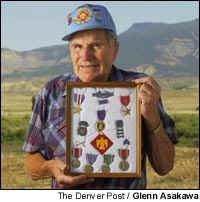

Felix Sparks, retired brigadier general of the Colorado National Guard, is nearing 90 years old, and his health is deteriorating rapidly. But before he dies, his buddies want to give the "soldier's soldier" a final tribute: the Distinguished Service Cross, the second-highest medal, next to the Medal of Honor, for saving three wounded GIs during World War II. Hidden in the freezing, snowy thicket of the French forest, the SS machine gunner stood in a foxhole with his finger on the trigger. From the hatch of a war-beaten tank, Lt. Col. Felix Sparks looked out into the trees, near what was left of his battalion, knowing he was already in the sights of a gun. Sparks surveyed the forest and figured that was where he would die. In the past 19 months, the 27-year-old had slogged his way through the bloody battles in the torturous caves of Anzio, Italy - where he was one of only two men in his company to survive. He had already earned a Silver Star for bravery and two Purple Hearts after being shot through the stomach and having his liver lacerated by shrapnel. Since landing in North Africa nearly two years earlier, he had bonded with a group of farm boys from Colorado, and watched most of them perish. Then in January 1945, he found himself near a place called Reipertswiller, in a battle most Americans would never hear about, as the Germans struggled to earn a small victory after their defeat in the Battle of the Bulge. Even after months of continuous combat, the fighting in the forest was like nothing Sparks had ever seen. Searing shrapnel rained from tree bursts - scattering branches, stumps and jagged hunks of metal as both sides hurled artillery. He requested permission to withdraw his troops to save their lives, but the request was denied. His unit was trapped in the forest, nearly surrounded. On Jan. 18, Sparks opened the hatch of his tank and saw two wounded American GIs lying less than 100 yards away. He knew the Germans were within easy firing range, and if he left the tank, he would be a clear target. Sparks had seen enough. He climbed out of the tank and headed for the wounded men. His only weapon - a .45-caliber pistol - remained holstered. Camouflaged within the trees, the German machine gunner with the telltale SS lightning bolts on his collar was ready to fire. "Wait," his squad leader told him in German, as he eyed Sparks through his binoculars. "Let's see what he's up to." As the Germans watched, Sparks ran to one of the wounded soldiers and began dragging him back to the tank. Two of his soldiers also climbed from the tank and helped him bring the wounded man onto the bow. Then Sparks left for the next man, whose leg had been shattered by a machine-gun round, and dragged him to the tank, where they made him a splint out of tree branches, a rifle and a machine-gun belt. "Can I come out?" another GI yelled. "Make a break for it," Sparks shouted back. After dragging the last man to the tank, Sparks climbed inside and backed it down to the forward command post, delivering the three wounded men to medics and providing cover for other soldiers who followed under the protection of the tanks. It was his only success at Reipertswiller. In three days of fighting, 158 enlisted soldiers were killed, including six officers. Three hundred men were wounded and 426 were captured - the worst battle of the war for the Colorado-based 157th Infantry Regiment. For much of the rest of his life, Sparks would wonder about what happened on that hill, how he lost nearly an entire battalion, and why no bullet ever found him. "Why?" he would ask himself. "Why didn't they shoot me?" More than five decades later, he has finally found an answer. 'Surprised I'm still alive' At 89 years old, Brig. Gen. Felix Sparks, once again, has seen enough. "It's hell lying here in bed all the time," he said from the modest Lakewood home he's owned for the past 50 years. "This is my life now - not much of one." For the most part, those sentiments fill his days - everything but his mind is frail. His once-bellowing voice now wavers from bulldog jowls that shake when he's angry. His bulbous nose is framed by long ears and wisps of gray hair. For the past several months, he has spent nearly all his time in bed, wrapped in flannel sheets, wearing blue pinstripe pajamas, waiting for the end. "Most of my men are dead now," he said. "I'm surprised I'm still alive." He may be the only one. As everyone who knows him is well aware, Felix Sparks is somewhat of an expert on cheating death. After the battle of Reipertswiller, Sparks' war was hardly over. He battled all the way to the Dachau concentration camp, where he was one of the first Americans to see the horrors that existed there. After surviving more than 500 days of combat, he would later return to Colorado to personally console the families of his men - and promise them he would not forget. A Texas native raised in Arizona, Sparks admired Colorado before he saw it. During the war, he reveled in his soldiers' descriptions of their hometowns, the mountains - and their fortitude. In adopting their home as his own, he would become a Colorado icon. After the war, he entered the University of Colorado, earned a law degree and, at 38, was appointed as the youngest member of the Colorado Supreme Court. He went on to serve on the Colorado Water Conservation Board and continued in the Colorado National Guard until retiring as a brigadier general in 1977. To the aging men in the 157th, however, the general remains "a soldier's soldier" - one of the few commanders who led from the front. And by forming the 157th Infantry Association, he kept their history alive. Before he dies, his men say, Felix Sparks deserves one more honor - one that remains mired in red tape in Washington, D.C. - 62 years overdue. Their salvation may come in the unlikeliest of eyewitnesses: The man with the binoculars in the SS uniform. Haunted by the battle The citation for the Distinguished Service Cross reads, in part, "Colonel Sparks' gallantry, courage, fortitude, initiative and complete devotion to the men under his command reflect the finest traditions of the United States Army and merit highest commendation." Despite the recommendation, Sparks never received the Distinguished Service Cross, the second-highest military award next to the Medal of Honor. To him, it doesn't matter. "Medals, what are they?" he asked. "I don't need any more." For decades after the war, Sparks never displayed his military honors. Only recently, his wife searched around in his dresser drawers until she found them. Today, they are mounted in his home near a plaque that he says is just as important as any battlefield recognition - one that recognizes the woman who has supported him for the past 65 years - a plaque dedicated to Mary Sparks that reads, "Behind every great man there is a great woman." He looked over at the tiny, soft-spoken, white-haired woman who stands half his height, but who he says has just as much strength - a woman whose care, along with that of his son, Scott, has allowed him to stay at home while he remains mostly immobile. "She had a baby the day after I left (for the war). I didn't see him until he was 2 1/2 years old," Sparks said. "I wouldn't be here without her." In his home, he keeps a replica of the logo of the 157th Regiment, and the motto the unit has carried since the Spanish-American War: "Eager for Duty." When he looks back at his own war, he still remembers the names of the men he lost in battle and all their hometowns. Of all the battles, though, he says he will never shake what he calls the "stupidity" that was the Battle of Reipertswiller. At the beginning of the battle, Sparks was directed to take a hill, along with three other battalions. The 157th was the only one to reach its objective, leaving the men exposed. "I requested permission to withdraw," Sparks said. "Through the radio, the transmission came back that the commanding general said, 'No, that would demonstrate weakness in the face of the enemy.' " From his bedside, those bulldog jowls shook again. "It would show weakness?" he nearly shouted. "Jesus Christ! We WERE weak!" He looked away. "I lost so damn many men. I lost the whole battalion. I never really have gotten over it," he said. "I never should have been in that position. It was a complete failure - well, except for those three men I got out." When he later met the general who refused to let him withdraw, Sparks, as usual, said exactly what he thought. "I said, 'If I was in that position again, I would have disobeyed your orders and withdrawn anyway,' " he said. He paused, then chuckled. "Well, I made an enemy there," he said. "Generals aren't the types to take an insult from a lieutenant colonel." Later, that same general denied the recommendation for the Distinguished Service Cross - a decision Sparks' men and some military historians say was politically motivated retribution. Instead, the medal for Sparks was downgraded to a Silver Star. The argument over the medal didn't haunt Sparks as much as the battle itself, and that day at the end, when the Germans didn't kill him. "They never fired on me. Not a round. Not a ROUND," he said. "Why?" Enemy in awe For more than five decades, the answer remained concealed in a handwritten journal, carried by a man who would never again don his uniform - a man who could not tell his own son about his role in the war. The man had first written his journal in a U.S. prisoner-of-war camp. The memoir begins with his life in Germany and how he joined the Waffen-SS, Hitler's elite German combat force, and how he spent most of his time on the Russian front. The journal remained concealed until 2002, when, through a connection with a military historian, his words were published in the book, Black Edelweiss: A Memoir of Combat and Conscience By A Soldier of the Waffen-SS. The book details battle after battle, until, on Page 188, the SS officer recounts an amazing scene from the forests of Reipertswiller: "Suddenly, the turret of the second tank opened and out jumped a single man. Watching through my binoculars, I thought him to be an officer. Ignoring the danger he was exposing himself to, he hurried over to the hollow where the infantry squad was trapped, helped some wounded men to reach the tank and loaded them on the deck, one after the other. Stunned, we followed this extraordinary rescue action without firing a single shot. The officer jumped back into the tank, spun around on his tracks, and dashed back to the rear. Those of us witnessing the scene, whether nearby or more distant, instinctively felt there was no honor to be won by firing on this death-defying act of comradeship." In the book, the German soldier says he joined the SS to battle Bolshevism and had no knowledge of the atrocities committed by some who wore the uniform - atrocities that, in the Nuremberg trials, would brand the Waffen-SS as a "criminal organization." Though the man claims he knew about the concentration camps, he writes that he did not know about the exterminations of the Jewish people. Still, he wrestles in his mind about whether he should have been able to make the connection after seeing hollow-eyed prisoners at a railway station - an image he says still haunts him. If the common soldier knew of the atrocities inside the camps, he maintains, they never would have given their lives for Hitler. In a telephone interview from his home in Germany, the man who uses the pen name Johann Voss - he refuses to allow his -real name to be published for fear of retribution - said he still remembers the scene at Reipertswiller. "My (machine gunner) had his finger on the trigger. But both of us said, 'Wait a minute, wait a minute, let's see what happens.' We were very much astonished," Voss said. "One could see he was up to something, and we didn't know what. Instead of just gunning him down, we were curious what was going on there. "When we saw these wounded dragged from that hollow and put on the deck of the tank, it was out of the question to open fire on these people struggling for life." For those trying to secure Sparks with evidence to reinstate the Distinguished Service Cross, the words of the enemy were just the ammunition they needed. Death of a medic Inside the Sparks home in Lakewood, Maj. Gen. Mason Whitney shook the hand of the man whose footsteps he followed. "How are you doing, general?" asked Whitney, adjutant general of the Colorado National Guard, on a recent visit. "Not too good," Sparks replied. "You look pretty well," said Whitney, who is also about to retire from the Guard. "I might look pretty well, but I can't walk," Sparks said. "Well, it's overrated," Whitney said. Sparks, who commanded the Colorado National Guard from 1969 until 1977, is credited with energizing it with a sense of leadership and history. In 2001, the Guard dedicated its armory in his honor, creating a museum filled with artifacts from the 157th Regiment. "That's where (new soldiers) receive their initial briefings," Whitney said. "When I talk to them about some of the things they're becoming a part of, I tell them about the heritage." Whitney and his staff - including public affairs officer Lt. Col. Barbara Wickham - have played a key role in assembling a request that would reconsider the Distinguished Service Cross for Sparks. "It may not mean very much in terms of having another award to put on a uniform or put in a shadowbox," Whitney said. "But people should be recognized for the deeds that they do. It should have been done in the first place." Sparks shook his head. "As far as bravery is concerned, I had just lost all my men. I didn't care if I got killed or not," he said. "It was an act of either extreme bravery or extreme ignorance. God, I was tired. Lack of sleep really got me." Still, as he looks back at the Germans who never fired on him, he can't forget the day they did. It was in Italy, he said, as Sparks and his men sought protection behind a stone wall. The Germans attacked, and Sparks' men shot a German captain, but the man did not die. Instead, he lay on the ground, moaning. "My medic, Jack Turner from Lamar, he said, 'I want to go get him,' " Sparks remembered. "I said, 'No you're not! No you don't!' " The German continued to moan. Eventually, Sparks drifted off to sleep. When he awoke, he saw Turner scrambling over to help the German captain. "He had the Red Cross armband on, and just as he got near that injured German, they gunned him down. They cut him in half with machine-gun fire. I never will forget that. They killed him," Sparks said. "I don't know why he went out there. I don't know why they shot him. Jack Turner. Killed him deader than hell." Sparks eyes glistened, as close as he comes to tears. "I went down to see his folks down in Lamar after the war," he said. "He was a good man." The two generals sat quietly for a minute. "Something I often wondered about in the war," Sparks said. "When I was a company commander or a battalion commander and we'd been ordered to attack, each time we made an attack, a lot of the soldiers would know they would be killed. But, by God, they would go. I told them to go and they went. "They just went. Into death. The American soldier." Whitney, a Vietnam veteran, nodded at the general. "I think Robert E. Lee had something to say about that," he said. "Before Gettysburg, he said that being a general of an army is probably the best and worst of all things. Because you have to be willing to kill that thing that you love the most." 'This is for the regiment' The process of the military awards board involves yet another battle - this time, through forests of paperwork. With the new information from Voss' account, the official reconsideration application was submitted in May and has since cleared several hurdles. Still, there are several more to go, and Sparks' friends wonder if he'll last as long as the process, which could take another year. Military historian Hugh Foster, a Vietnam veteran who was made an honorary member of the 157th Regiment, has spent much of his life since the war securing medals for service members who never received them. For Sparks' application, Foster dug up dozens of pages from the U.S. National Archives to support the award, including statements from eyewitnesses who have since died. It's the statement from the living eyewitness, he said, that stands out. "I think (Voss' account) adds a lot to this," said Foster, who is writing a book about the battle of Reipertswiller. "When he first wrote this stuff down, he was in a prisoner-of-war camp, just expressing his true awe. I think it's quite significant." The paperwork must clear investigative councils before being approved by a collection of generals, and finally approved by the secretary of the Army. The application is sponsored by the office of U.S. Sen. Wayne Allard, R-Loveland, who, according to a spokesman, soon plans to deliver the request to the top levels of the military in hopes of expediting the process. After seeing the camaraderie at the reunions of the 157th Regiment Association - reunions made possible by Sparks - Foster says he knows who will appreciate the award the most. "This is for the guys. Sparks couldn't care less. This is for the regiment," Foster said. "They look at him in awe - absolute awe. He's viewed as an absolute movie star." For 86-year-old Jack Hallowell, the slowness of the process gets more difficult each time he visits his bedridden former commander. "It's been hard on me - hard on all of us," said Hallowell, who served under Sparks in Italy and has remained his good friend. "We've missed him." Hallowell is planning for the next reunion of the 157th - which has roughly 800 members, though only a handful are left from Colorado, since the bulk of the state's contingent was killed in Italy - and he says he has one hope when they meet again in October in Colorado Springs. "If we can get him that medal, we can get him in a wheelchair and bring him down there," Hallowell said. "Some guys keep saying, 'This is the last reunion.' We always wonder if it's the last." Seen enough killing Even after his retirement, Sparks continued to fight. In the 1990s, he made headlines after his grandson was killed in a drive-by shooting and Sparks formed an anti-handgun group and battled the National Rifle Association to push through strict gun laws for minors that remain on the books. After the war, he decided he had seen enough killing - when his buddies would go deer hunting, he went along, but he didn't carry a rifle. He remains a critic of the war in Iraq. Until recently, he also continued to speak out at Holocaust remembrance ceremonies, challenging deniers to tell him that what he saw inside Dachau didn't happen. "Tell that to my face," he would shout. As for the SS soldier who spared his life, Sparks has yet to speak to Voss, but says he holds no grudges toward him - or most of the other Germans on the front. "I never had any animosity toward the German soldiers. They were just doing their job," he said. "It's those sons of bitches like Hitler that were the problem." Voss said he hopes Sparks receives the Distinguished Service Cross. Still, he said, he laments that the dead Germans he fought with on the front will likely remain largely forgotten. "Our world has perished," he wrote in his memoir from the prisoner-of-war camp. "A new world dawns, one in which our values are utterly discredited, and we will be met with hatred or distinct reserve for our past. Come on, I say, it's not without reason, let's face it! What counts is our future and what we are going to do with it. . . . Yet there can be no release from our loyalty to our dead, from our duty to stand up for them and to ensure that their remembrance and their honor will remain untarnished. They, like all the others fallen in the war or murdered through racial fanaticism, must be remembered as a solemn warning never to let it happen again. . . . The cause for which they died may have been corrupt and the symbols under which they fought may have been vile, but their profound selflessness, their loyalty to their country, and their final sacrifice possess a value of their own; it is the spirit of youth without which a nation cannot live." In his own epilogue written to the men of the 157th in one of his newsletters - later published in the book, Sparks, by Emajean Buechner, the general offered his own summation. "During the course of World War II, I lived through three traumatic events which still continue to haunt me - the Battle of Reipertswiller, the Battle at the Caves of Anzio and the liberation of Dachau. I know that the other soldiers of the regiment who participated in any or all of these events must have the same haunting memories. . . . I suppose that all that can be said at this point in time is that how fragile is the thread of life and how futile is the waging of war." As Sparks laid on his bed, preparing for his physical therapy, he thought back to the forest. "I've been back to that hill three or four times since," he said. "You can still see the foxholes, spent cartridges and the signs of war, but now it's a peaceful forest, just peaceful, that's all." Now that he has the answer to his lifelong question of why the Germans allowed him to rescue his men, he doesn't hesitate when asked if the roles were reversed. What if it were Sparks in the foxhole, and he had his finger on the trigger? What if it were a German SS officer jumping off the tank in the war-shredded forest? "If it were me," Sparks said, "I would have shot him." History of the 157th Infantry Regiment 1862: Colorado Volunteers help defeat Confederate soldiers at LaGlorieta Pass, near Santa Fe. 1879: 1st Colorado Infantry Battalion is born. 1898: 1st Colorado Infantry participates in amphibious assaultsnear Manila during the Spanish-American War. 1916: The 1st Colorado Infantry is sent to the border of Arizonaand Mexico, where soldiers battled Pancho Villa's troops. 1917-1918: 1st Colorado Infantry officially changes designationto 157th Infantry and is assigned to 79th Infantry Brigade, 40thInfantry Division. The 157th served in France during World War I as part of the 40th (Sunset) Division. 1940: The regiment-made up primarily of farm boys from tinytowns throughout Colorado - is folded into the 45th Infantry Division and mustered into service at Fort Sill, Okla., and later toCamp Barkley, near Abilene, Texas, to prepare for action in World War II. 1943: The 157th arrives in North Africa, and sees its first combat on the beaches of Sicily, then Salerno, where Cpl. James D. Slaton earned the regiment's first Medal of Honor by wiping out threeGerman machine gun nests with rifle fire, hand grenades and hisbayonet. 1944: The regiment suffers heavy losses in the bloody battlesat "the caves" on the beachhead of Anzio. Of all the men in E Company - most of them from Lamar - only Capt. Felix Sparks and oneotherman survived. That man was later killed in combat. The regimentbattled to Rome, then through the plains and mountains of France, on its way to Germany. 1945: The year started with the regiment's worst defeat, in abattle near the Alsace village of Reipertswiller. In April, a group led by Sparks helped liberate the concentration camp at Dachau.Munich fell the next day. In its 667 days overseas, the regiment wasin battle 511 days. During World War II, its soldiers were awardedfour Medals of Honor, 20 Distinguished Service Crosses, 376 Silver Stars, 1,054 Bronze Stars and 1,694 Purple Hearts. On Dec. 7, 1946, the 157th was deactivated from World War II. 1947: Sparks joins the Colorado National Guard as the executiveofficer of the 157th Regimental Combat Team, which soon was renamed the 157th Field Artillery Unit of the Colorado Army National Guard. 1957: Governor designates U.S. 40 through Colorado as "The 157th Infantry Highway." 1961: The 157th is reactivated under Sparks during the BerlinCrisis and sent to Fort Sill, Okla. 1968: Sparks once again takes command of the Colorado ArmyNational Guard, rising to the rank of brigadier general before retiring in 1977. 2001: In August, the Colorado Army National Guard dedicates itsnew armory in honor of Felix Sparks. Twelve days later, in the wake of the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, soldiers from the 157thbegin aiding in "Operation Noble Eagle," guarding Denver International Airport and other possible targets. 2004: The last of more than 400 157th soldiers are released after a year of guarding Air Force bases and the Pueblo Chemical Depot. 2006: Soldiers from the 157th spend a month in New Orleans, helping to aid victims of Hurricane Katrina. 2007: Soldiers aid ranchers after a blizzard strands thousandsof cattle in southeastern Colorado. At the request of AdjutantGeneral Mason Whitney, a new infantry unit is expected to re-assembleas part of the Colorado Army National Guard - much to the delight of Brig. Gen. Sparks. "I went to hell and back with the infantry," he said. "It will be good to have them back home." SOURCES: Sparks: The Combat Diary of a Battalion Commander (Rifle) WWII by Emajean Buechner (Thunderbird Press), Lt. Col. Hugh Foster (Ret), Sgt. 1st Class David Schmidt and Brig. Gen. Felix Sparks. sheelerj@RockyMountainNews.com or 303-954-2561

Our reunion officially runs

from Wednesday September 8th through Sunday 12th. Room rates are

good for 3 days before and three days after the official reunion program dates, based on

availability. We will be staying at the Four Points Sheraton – Denver Cherry Creek

located at 600 S. Colorado Boulevard, Denver, Colorado. For those of you driving to the

reunion the hotel offers plenty of free parking. The room rate is just $79, plus tax per

night which is excellent for this hotel. Please make your hotel reservations NOW by

calling the hotel directly at 303-757-3341. You may request specific room types, handicap

rooms, etc. when you call. Remember the check in time is 3:00 PM; you should not expect to

get into your room before then. Make your hotel reservations

NOW. We have a limited number of rooms and due to the popularity of this city the hotel

will sell out fast. Be sure to ask for the 157th Infantry reunion rate and

request a specific room if needed. Ask the hotel for directions if you need them. Reunion

forms and a roster of attendees can be found on our private website at:

www.militaryreunionplanners.com/157th.htm

HIGHLIGHTS OF THE 157TH INFANTRY

ASSOCIATION REUNION - VIRGINIA BEACH, VA. 2002 Our 2002 reunion was held 2

– 6 October at the Holiday Inn Executive Center, Virginia Beach, VA. Seventy

–three Association members who are veterans of the Regiment and the 158th

Field Artillery Battalion, most accompanied by wives, children and even a girlfriend or

two (!) were in attendance. Present also and warmly welcomed were 18 family members of

soldiers who were Killed In Action or who died since the war. Seven reenactors joined us

for the entirety of the reunion, and worked tirelessly on a number of difficult projects,

most particularly in manning and stocking the well-used bar – in recognition of their

great assistance and deep interest in the history of the regiment and the 158th

FA Battalion, all of them have been inducted as full members of the Association. All companies and batteries

were represented by those attending, except for C Battery and Service Battery. At least

two first-time attendees surfaced at the reunion, both in the company of their lovely

wives: Mason Miller, who served with the Regimental Band, and Warren Wall, a medic who

served with B Company. There were a number of

off-site events and tours, including cruises of the Norfolk Harbor and trips to Colonial

Williamsburg and the Norfolk Navy Base. Through it all, Ray and Dixie Casey, of National

Reunion Planners, really took the strain off the attendees, by doing all of the

coordination and most of the administrative work. They were, however, more than ably

assisted by Brenda Baker (daughter of the late Russell Freshour, of C Company), whose tact

and hospitality were sorely tested, but did not fail her in operation of the registration

desk and in the many other duties she took upon herself. Our banquet was held on

Saturday evening, 5 October, and was attended by well over 200 persons. Following the

posting of the colors by reenactors in WWII uniforms, toasts were given to the Army, the

Regiment, the American soldier, absent comrades and to the ladies. Following an

exceptionally good meal, Van T. Barfoot and our outgoing President, Chan Rogers made brief

remarks. The guest speaker was Navy Captain Mark Nesselrode, Commanding Officer of the

Aegis Class missile cruiser USS Anzio (CG68) Yet another of the touching chance encounters that have become frequent at recent reunions took place during the banquet, though it was unnoticed by most people. During Captain Nesselrode’s speech, our Recording Secretary, Hugh Foster, noticed a “lost-looking” man peering into the banquet room through the main door. It turned out that the man was passing by the hotel on his way home from work and had seen mention of the 157th Infantry Association on the hotel’s marquee. On the spur of the moment, he decided to drop in to see if there was anyone in attendance who knew his father, Pvt. James T. Warnick, of G Company. Hugh was able to put him in contact with five men of G Company, including Ken Rogers. The ensuing conversation quickly proved profitable for the junior Warnick, for Ken was able to relate that his dad and he had been captured together on 4 June 1944 and both men were among a group who escaped and made it back to the company after several days. It is, indeed, a small world. Ralph Fink once again

stepped forward by volunteering to conduct the Memorial Service, in which we remembered

and honored 32 members known to have passed away since our last reunion. During the business meeting, the members in attendance voted to hold the next reunion in Tampa, and elected a new slate of Association officers. Our new President is Gordon Kinley, and Al Panebianco was elected to the post of Vice President. Treasurer Bill Lyford and Recording Secretary Hugh Foster both volunteered to remain in their posts and were confirmed in those positions by unanimous vote.

HIGHLIGHTS OF THE 157TH REGIMENT REUNION - DENVER, CO. 2001. This article appeared in the Denver Post, August 26, 2001.

This was the worst. This was living with death every hour of the day and night, and as close to hell as any man would want to come. This was Anzio, and this was the worst. - from "History of the 157th Infantry" When the Germans attacked, they came in screaming. Hollering. Like they were drunk. On the front line, the men of E Company silenced the shouts with gunfire. Then they heard another rumble. From his muddy foxhole, a soldier from southeastern Colorado looked up. "Tanks," thought Clarence Reissig. "They look like rolling castles." Many of the soldiers of E Company had known each other since they were kids, working on the farms in eastern Colorado near Lamar. A few hundred yards back from the front were the men of F Company, mustered mainly from Boulder, along with Longmont's G Company. Nearby were groups spanning the state, from Fruita to Burlington, Brush to Craig. Known as the Colorado National Guard Regiment, they fought as the 157th Infantry. On their uniforms they wore the same motto: "Eager for Duty." As the artillery shells fell, the men of the 157th felt the ground shake inside the foxholes. Some were catapulted out of the holes by the blasts. The shock was strong enough to cause instant nosebleeds. The earth was torn apart. The men were torn apart. Supply lines were cut, and thirsty soldiers drank water from red streams, boiling away the blood. When E Company began the battle at the Anzio beachhead in Italy, it was nearly 200 men strong. After more than a week of brutal fighting, only two men would walk away. One of them would later die in battle. The other would make it all the way through Germany and the liberation of the Dachau concentration camp, opening the gates to new nightmares. "These guys were really the unsung heroes of World War II from Colorado," says Flint Whitlock, author of "The Rock of Anzio," a 1998 book that has a history of the regiment. "Not many people outside their families know what they did." As the men of the 157th gather this week in Denver, the old veterans will serve as a living reminder of those stories born in Colorado and played out during 511 days of combat, as close to hell as any man would want to come.

"What a miscalculation' From a couch at his home in Lakewood, an 84-year-old man in a Hawaiian shirt takes himself back to the place where a 26-year-old captain lost his entire company. "Anzio," Felix Sparks says. "What an abortion. What a miscalculation." Following its initial landing in North Africa, the 157th lost men at Sicily and Salerno. After storming the beachhead at Anzio, Sparks' company held its ground near a crucial roadway. They were pushed into nearby caves, and at the end of it, Sparks stumbled out of the fighting almost unrecognizable - muddy, dehydrated and already growing a thick black beard. The men found him a foxhole and put him to sleep. "Life is mostly luck. It isn't planned," Sparks says. "You take what you can, and you take advantage of it." During an interview in his home that lasts more than six hours, Sparks never moves from the couch. Despite a slew of health problems over the past few years, he never tires of the stories. His bulldog jowls shake when he gets mad; he swears like he's still in the trenches as he recounts military blunders from headquarters that got his men killed. When he talks of the camaraderie, a growling chuckle shakes his body with the same intensity. A Texas native raised in Arizona, he joined the Army because he thought it was his last hope after the copper mines closed. Likewise, many of the men from small Colorado towns had joined the National Guard during the Great Depression, thankful for a couple more dollars a week. During World War II, those burly Colorado farm boys from the National Guard would form the backbone of the 157th. When they set sail from Virginia on June 8, 1943, Sparks estimates that of the 3,200 men in the regiment's initial invasion force, about 2,000 came from Colorado. Of that number, he figures that about 90 percent were injured, killed or taken prisoner by the end of the war. Sparks was one of the few to make it all the way, in the process performing daring battlefield rescues that would earn him Silver Stars for bravery and two Purple Hearts. At the end of the initial fighting in Anzio, when Sparks awoke from the foxhole, the battalion was awarded a presidential citation for its role in saving the beachhead. He was then given 10 days to train 700 raw recruits from all over the United States. At the time, D-Day was still months away. In upcoming battles in France and Germany during the following year, the regiment would leave hundreds of men in cemeteries that their parents, wives and children would never see. But just as the men from the 157th would figure the worst was over, that the war was won, they would receive their last major assignment: "Tomorrow the notorious concentration camp at Dachau will be in our zone of action. When captured, nothing is to be disturbed. International commissions will move in to investigate when the fighting ceases."

Boxcars full of bodies It started with the boxcars, and one dead man among thousands. "The thing that we saw first was 39 railway cars all full of dead bodies," Sparks remembers. "We didn't know what the hell they were doing there." In an attempt to hide prisoners as the nearby Buchenwald camp was captured, the prisoners were crammed into the railcars headed for Dachau. Most of them suffocated along the way. "One of 'em had had enough strength to crawl out of one of those boxcars," Sparks says. "A German soldier had crushed his skull with a rifle butt. His brains were all over. That got a lot of the men mad. Some of them were crying. Some of them were cussing. But most men didn't say anything. They couldn't believe what they were seeing. "That was our initiation. We still had more to come once we got inside." Once inside the gates, the men saw what they called a new level of hell. Then it all broke loose. "That was one of the worst days of my life," Sparks said. "It's like being in a bad dream. All those dead bodies. Maggots. The smell. To see those naked bodies stacked up like cordwood. It's hard to believe you're actually there." For some of the men, emotions boiled to fury. While Sparks was at another part of the camp, dozens of the SS soldiers were lined up and shot. When he heard the gunfire, Sparks ran back, firing his pistol in the air to stop the executions. Though many argued that the SS officers deserved a fate worse than the firing squad, Sparks was later called into Gen. George Patton's office to answer for the actions of his men. He recounted the scene in a newsletter for the 157th Association, beginning with his request to Patton to give his side of the story. "The general paused for a moment and then said, "There is no point in an explanation, I have already had these charges investigated and they're a bunch of crap. I'm going to tear up these g------ papers on you and your men,'" Sparks recounted. "With a flourish, he tore up the papers lying in front of him and threw them in the wastebasket. "He then said, "You have been a damn fine soldier. Now go home.'"

Moved to Colorado Sparks had never seen Colorado, but he knew what it looked like. He'd heard his soldiers talking about home. After the war, he moved his family to the state where so many of his men never returned, and graduated from CU's law school. He worked as an attorney and ultimately was named a Colorado Supreme Court justice. He returned to the National Guard, serving during the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962, and retired a brigadier general. In 1993, gunfire once again brought him out of retirement: His grandson was killed in a drive-by shooting, and Sparks formed a group credited with making it illegal for minors to own handguns. On Thursday, the Colorado Army National Guard will dedicate its Centennial Armory to Sparks. The men of the 157th will be there, as part of their annual reunion that Sparks started in 1975. Those men - 1,100 at last count - are the last of the 157th Infantry. "Numbers don't mean a hell of a lot to anybody anymore. And there's only a handful of men left here in the state who served with the 157th," Sparks says. "Not that many people know (about the regiment). But the people in the small towns know. There are a lot of widows. A lot of people killed." For Sparks, those widows' faces reflect in the same pool of memories as his men. In 1945, when he first saw Colorado, he traveled to the small towns he had heard about in the foxholes and met the widows. "There was one widow in Fort Morgan. I went to see her after her husband was killed. He was a good man. He married a girl he knew in high school. Rose. Rose was her name," Sparks remembers. "They had two kids in rapid succession, and then he was killed. I was sitting in the living room, and the two little kids were there. She said, "This man knows Daddy.' Two little tiny kids. They didn't know what the hell she was talking about." For the first time in several hours, the old general closes his eyes, catching the words in his throat. "That really got to me," he says finally. ""This man knows Daddy.'" Vere WilliamsGot a 'funny feeling' when danger was near

As the amphibious boat pulled onto the beach on the southern coast of France, Vere Williams had one of his funny feelings. Funny in a bad way. By then Williams had already been wounded four times. Before he felt hot metal sear his flesh, he would get one of those strange feelings. "You have the feeling that something's going to happen," he said. "Even when I was growing up on the farm, I had the same feeling." Back in Snyder in northeastern Colorado, he said, the feeling led him to jump off tractors just before a bolt was coming loose. On the beach in France, he convinced his injured comrades to drag themselves away from the area, just before another explosion obliterated the place where they had been. After another stay in the hospital, he was back on the front line. "I don't know," he says. "I figure I must have three or four guardian angels looking out for me." On Halloween 1944, 10 miles from the German border, he had the feeling again. That afternoon, a bullet shattered his arm. He would spend the rest of the war in a hospital. These days, he lives in a small trailer home in Whitewater, south of Grand Junction, where he keeps his stories for anyone who asks. He keeps them near his Purple Hearts. "When they brought me onto the ward with the last wound, they brought me next to the nurse's station," he remembered. "One of the nurses would come in and talk to me whenever she got a chance. She said, "You know, whenever I ask the boys what it's like on the front lines, all they say is, "It's hell up there." Well, I know it's hell up there, I can see what you boys come here looking like.' But what's it like?'" Over the next several hours, the next several days, Williams told her about the fighting, the freezing, and the bodies. He told her how his platoon that started with 14 men had seen 65 replacement soldiers since the beginning of the war. He told her about the feeling right before you get shot. "I told her what happened," Williams said. "She said, "I can see, now, why they call it hell.'" Otis VanderpoolYouth from Olathe lost older brother

When Otis and Ervin Vanderpool left the cornfields of Olathe for the army, they had never traveled beyond western Colorado. At 21 years old, Otis was still working on the family farm. Ervin, his older brother by 10 years, figured he had better join alongside his little brother. Everyone in K Company remembered the Vanderpools. Ervin was known for buying candy bars at the PX and then reselling them on the battlefield for 5 cents more than he paid. He was also known for sticking next to his little brother. Otis was quick and smart for his age and was a sergeant during the bulk of the fighting.

During a battle in the Vosges Mountains of France, near the German border, battalion commander Felix Sparks heard that K Company was in trouble and ran over to see what he could do. He rushed up a hill, only to see Otis on a stretcher, his leg blown off at the knee. When he made it to the front, he never told Ervin about his brother's injury. He didn't have time. The older brother was shot in the stomach and died on the battlefield. "I kick myself for not promoting (Ervin) when I should have," Sparks said. "If I would have promoted him, he wouldn't have been in that battle." When Otis hears the story these days, he says Sparks shouldn't trouble himself. Other officers had also talked of promoting Ervin, sending him to battalion headquarters, but he refused to listen. "He wouldn't accept a promotion," Otis said of his brother. "He wanted to stay near me." Jack HallowellFate intervened with a typewriter

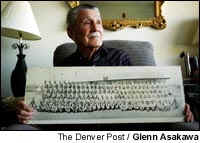

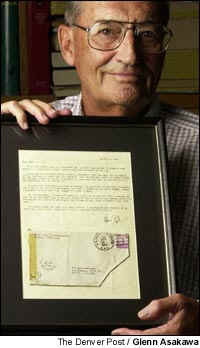

Carrying the metallic mouth of a 60mm mortar cannon, Jack Hallowell made it through the front lines at Sicily and Salerno, and was headed for the beachhead at Anzio. That's when a Royal portable typewriter saved his life. "The (commanding officer) said, "Well, we've got a long war, we should probably have someone writing a history,'" Hallowell says from his apartment in Lakewood. "They found out I had a journalism degree from the University of Montana. I wasn't a historian, but writing that history sounded a lot better than carrying that mortar." As Hallowell pored through journals at regimental headquarters, his company was wiped out at Anzio - only two men walked away. "My fate would have been different if I hadn't been sitting back there at HQ with a Royal," he says. "I do have some conscience about not being with them." But if it weren't for Hallowell and several other men, much of the history would have been lost. Hallowell followed the 157th from its training in the United States all the way through to Munich. Along the way, he found plenty of stories, along with a few mementos.

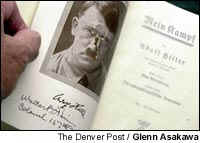

"How about this?" he says, pulling out a copy of "Mein Kampf" he took from the Dachau concentration camp. Soldiers from the regiment signed the book; one of them punched the photo of Hitler in the nose, ripping the paper. Since the war, he's put his German artifacts to peaceful uses: He uses an enemy soldier's spoon to eat his breakfast cereal; he uses a Nazi knife to dig up dandelions in his yard. And on his table is the work that rests on the shelves of the men he knew better than any historian, the work that Hallowell clack-clacked out with his heart and hands: "The History of the 157th Infantry."

|

|

©

Copyright 1999 - 2005. All Rights Reserved. Please contact the Webmaster with any questions or comments.