Memoirs

| Dachau | CMOH | Reunions | E-Mails | Memoirs |

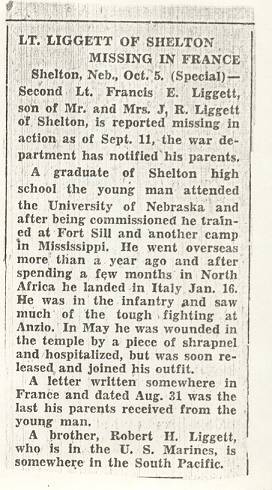

Mr. Panebianco, Allow me to introduce my self. My name is Burt Gloor and my wife (Mireille) and I have a second home in a tiny village 3km from Barjols, France. This past summer I had the wonderful experience to observe first hand the annual celebration of the liberation of Barjols by the 45th Infantry. (August 27th, 1945) It was a very moving experience and demonstrates the deep gratitude that the French hold for the 45th Infantry in Barjols. The celebration began with a convoy of original WW II jeeps, duece and a half, and trucks. All the men were dressed in American Army uniforms, wearing the insignia of the 45th. Even their pants were made of the original heavy wool. The small square was decorated with American, Canadian and French flags. It was interesting to see that they have passed on the tradition of remembrance to the younger generation. One woman hung out her laundry on the balcony in a red, white and blue pattern. I thought you would enjoy seeing these photos and to share with some of the other brave American soldiers who liberated France. I can now vouch for their sincere gratitude and hope I can add my sincere gratitude to the brave soldiers who fought not only for America but for freedom for Europe. Thank you. I will return to this celebration of remembrance as long as I live in Ponteves, France. Sincerely, Burt and MIreille Gloor NO---NOT YET

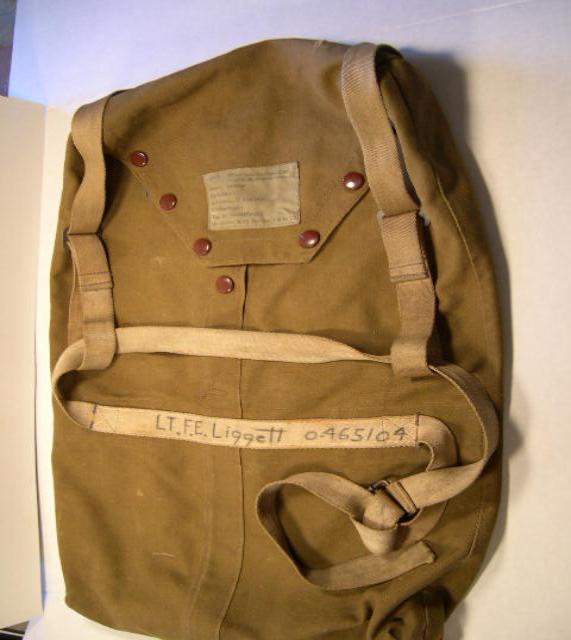

Military Memoirs by F. Eugene

Liggett

CHAPTER I In September 1938, I went to Lincoln, Nebraska where I enrolled at the University of Nebraska in the College of Agriculture. Participation in the Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) program was one of the required subjects in all the Land Grant Colleges in the U.S. for the first two years of college. At the end of this period we had the option of signing up for the next two years of advanced training. This would lead to a Reserve Commission as a second lieutenant in the US Army. At the College of Agriculture campus in Lincoln, we had a field artillery unit, so that is what I was trained for. On the city campus there were infantry and engineering units. In June of 1941 we were required to attend six weeks of artillery training at Ft. Leonard Wood in Missouri. Here we got our first experience of being in the Army—living in a barracks with others and all the various rules and regulations other soldiers in the Army live by. In June 1942, after my senior year of college and four years of ROTC, I received a commission as a Second Lieutenant in the Reserves. My Army serial number was O-465104. Because I had had to work my entire way through college with out any financial help, I still lacked a few hours of graduating, so they gave me a deferment for one more semester to complete the requirements to graduate. Immediately upon graduation in January 1943, I was called to active duty and went to Ft. Sill, Oklahoma. There I was assigned to a training battery to help train new enlisted recruits while I waited to attend an officer’s class at the Artillery School. After some time, I attended a four months long Battery Officer’s Course (BOC) which included about the same technical training as did Officers Candidate School (OCS), which commissioned officers from the ranks. The big difference was that we did not have all the BS that the OCS candidates were subjected to. After graduating from BOC, my classmates and I got orders to military assignments all over the US. Most of us got two-weeks leave so we could go home, or wherever, before reporting to our new duty station. Of course I headed back to Lincoln, Nebraska, where I had left the girl I had hoped and planned to marry - Enid (Skeets) Mundhenke. She was in nurses training. My parents, Jim and Estella Liggett, my sister, Freda, who was still in school, and my brother, Harold and his wife, Leona, with their small daughter, Janice, all lived in Shelton, Nebraska. My other brother, Bob, was in the USMC. It was hard to tell all of them goodbye when I had to leave to go to Camp Shelby, near Hattiesberg, MS. The 65th Infantry Division was being formed and there was a lot of competition among the officers for various positions and jobs. A good friend of mine, Merritt Plantz was also from Nebraska and had been with me in many classes at the Agriculture College since 1938. We were commissioned at the same time in 1942, and were both deferred to finish college. We were called to active duty at Ft. Sill at the same time. We were not in the same class but upon graduation, both of us were sent to Camp Shelby to be in the 65th Division. We were both assigned to the same artillery battalion, but to different batteries. I didn’t particularly like the outfit and as a means of getting out, I applied for Liaison Pilot Training. Liaison pilots flew the small Piper Cub planes used for observation and to adjust artillery fire. I had passed the physical exam and was waiting to be called to go to school, when the Battalion got orders to send a certain number of officers to North Africa and Italy as replacements. I was one of those with orders to report to Ft. Meade, MD to ship out. I didn’t have time to go home for another visit, but I did stop in Birmingham, Alabama to see my cousin, Esther (O’Neill) and Red Roberts and their small son. From there I went to Atlanta to visit Elsie (Van Winkle) Moye, another cousin. At Ft. Meade we had nothing to do but wait, so I went to NYC a couple times to visit Dwight Cherry, my former college roommate at NU. He was a medical student at Columbia Uni. and later became a doctor and surgeon. Also I got to go to Washington, DC and Baltimore several times. On a November night I got on a train with several hundred other replacements and went to Newport News, Virginia where we boarded the ship, the HMS Empress of Scotland. It was formerly an English passenger ship and was now used as a troop transport ship. There were about 6,000 of us on it, with the officers having staterooms, and the enlisted men bunking down in the holds. Because there was a significant threat from German U-boats, most ships crossing the Atlantic traveled in convoys, with navy escorts. However, as the Empress could steam at 35 knots, we went across as a lone ship. We went south to near the coast of Brazil, and then eastward along the Equator, and up the coast of Africa to Casablanca. However, out in the middle of the Atlantic we ran into nine German submarines. Our ship dropped a lot of depth charges. When these exploded, it sounded like someone on the outside of the ship’s hull, hitting us with a big sledgehammer. At the same time our ship changed to a zigzag course, changing direction every seven minutes. As a result, the big ship rolled to one side and then to the other, causing a lot of people, including myself, to get seasick. This was my first ship ride. I felt pretty lucky to be an officer, as we had a steward to wait on us in our staterooms- even to “draw my bath” as there was a big bathtub in my cabin. On the ship we had a big early Thanksgiving turkey dinner in the officers’ dining room. I had never seen so much silverware as was spread out on each side of our plates, or as many fancy dishes and glasses as graced the tables. Naturally, the food matched the surroundings, so it was one dinner I will always remember - quite a contrast to the next Thanksgiving dinner I was to have in prison camp. I felt sorry for the way the enlisted men were fed and were crowded into the holds below deck with such poor ventilation provided. Nobody could go out on deck at night as everything was “blacked out”. Finally, we pulled into the harbor at Casablanca. Here too, I had a new experience, as I watched men unloading coal on a ship next to us. The stevedores were like a steady stream of ants, carrying fiber baskets full of coal on their heads from the ship to wherever they dumped it We were taken outside of Casablanca to a “tent camp” surrounded with barbed wire fences. Guards continually patrolled to keep the Arabs from stealing stuff from us. They often shot several each night. The Arabs and kids were continually trying to beg, or steal whatever they could. It appeared that their most sought after clothing consisted of a blue GI barracks bag with two holes cut in the bottom for their legs and the drawstring or rope around their waist. Usually there was a GI’s name and serial number across his rear end. Another favorite, especially for the women, was a navy mattress cover with a hole cut in for their head and holes for each arm, with the mattress cover being worn as a dress. One night I went into town to the Automobile Club, which was the Officers Club. Navy and Army personnel from all over the world were there drinking and gambling. MP’s were stationed at about every gambling table, as the stakes were often quite high. I had learned my lesson and had not gambled any since first going to Ft. Sill. This lesson has lasted me a lifetime too. That night I got friendly with a Navy officer from Scotland. He was singing a song for what seemed like hours, with the last line of each verse ending with “there will always be an England for Scotland to defend”. From our camp outside of Casablanca we could watch the camel caravans coming in from the desert to the East of us. Here we had another Thanksgiving dinner with the cooks and help being Italian POW’s. We all got a good case of dysentery as a “bonus”. Finally, we boarded a train and headed toward Oran. There were numerous delays as some parts of rail line used electric trains and parts used old steam engines. At each stop, either day or night, the native Arabs came with all kinds of knives and swords, which they tried to sell or trade. It was sort of scary the way they flashed them around at us to get our attention. Oran was another interesting place with all the underground tunnels etc. Most of these were “off limits”, but down along the water (the Mediterranean) were the centuries-old places where slaves had been tied to iron rings fastened into walls of open caves in the rocks. Several of us went into a Muslim Mosque one day. We had to take off our shoes before going in. The women were on one side of the room and the men on the other side - all facing east and kneeling down praising Allah. By this time the war had ended in North Africa, the Allies had taken Sicily, and the fighting had moved to Italy. The rugged nature of the terrain north of Naples, the poor quality and lack of roads, and the adverse weather conditions created enormous problems for the combat soldiers. The few roads that existed in the mountains became muddy quagmires in the constant rain and snow. In many places it was impossible to use motor vehicles to transport men and supplies to the front lines, or to evacuate the wounded. Supplies had to be carried on the backs of soldiers or mules, and the wounded had to endure lengthy and painful movement on unsteady, bouncing litters. Word that men were being worn to exhaustion by the awful environment even before they got into combat filtered back to the replacement centers in North Africa, and it was wisely decided that we should be in better physical shape before being sent up to Italy. About 50 - 75 of us

officers were sent out in the desert somewhere near Sidea-Bela-Bes,

which was the headquarters of the French Foreign Legion. Here I learned

a lot of the tactics used by the Infantry. We used live ammunition,

which caused an occasional “unsafe” condition for the Arabs and

their sheep or goats when we encountered them in our maneuvers. At night

we slept in tents that we had erected. The training included a very

difficult obstacle course, tougher than I had seen anywhere else. With a

full pack and rifle, we crawled under barbed wire entanglements with

live machine gun fire only inches above us, over walls and through

various other obstacles, and crossed a river on a

Back in Oran in Dec. 1943 I had my picture taken at some little studio by a French lady. One pose - one shot, and that was all. I paid her and gave her the address to send one to the folks and one to Skeets. Later I was surprised to find out that she did, indeed send the pictures home instead of just pocketing the money. I now have the original picture she sent my parents. On New Years eve, 1943-44, several of us who had been together since we were at Ft. Meade, got some Pink Champagne, and I think that was the last time I ever got drunk. Shortly after that we got on a Liberty ship bound for Naples. Because so many ships were being sunk by German submarines, we were in a big convoy and sailed east along the African coast to Bizerte, and then past Malta and over to Sicily where we stopped shortly before going on to Naples. At about this time, Mt. Etna in Sicily was erupting and sending up a lot of black smoke and ash. Going through the Straits of Messina (between Sicily and Italy) the water was the roughest I ever saw. Our old Liberty Ship rolled from side to side and end to end. The screw (propeller) came up out of the water and it shook the whole ship. At the same time the bow went under water—then the reverse, with the bow up out of the water and the stern under. All the time it was rolling side to side. For some reason I did not get seasick though. Nobody could stand up or even walk around. We crawled, if need be, to get some C-rations to eat. All of us were glad to get off the ship. It had taken us 21 days to cross the Mediterranean from Oran to Naples. In Italy we went to a Replacement Depot north of Naples. From here we got to watch all the planes going to and coming from the bombing of the Monastery. We saw some of some of the B-17’s or B-24’s being shot down and also got to see several good dogfights between US and German fighter planes. A short time later several of us got orders to go up to Anzio as replacement officers for those who had been killed or wounded. The four of us who had been close friends since we first met at Ft. Meade were included in this group of replacements. Lt. Olsen and I went to the 45th Infantry Division. Lt. Hoffman went to the 36th Division and Lt. Hood went to the 3rd Division. Later Hood and Hoffman were killed, Olsen was badly wounded and I was captured. This was typical of most all of the 60 or 70 officers who had come over together. We were taken down to the docks at the Naples harbor to load up on assigned Liberty Ships to go to Anzio. I was walking along the dock when I met Warren Pavlat, a close acquaintance from the Agriculture College in Lincoln, Nebraska. He was now a naval officer on one of the Liberty Ships. He asked me to ride up to Anzio with him, so I went back and got permission to get off the ship I had been assigned to and to ride up with Pavlat on his ship. We sat up all night talking and renewing our friendship. The next morning, as we sat at anchor in the Anzio harbor, the Germans came over and bombed us. The ship that I had originally been on got a direct hit and, having been loaded mainly with gasoline and ammunition, it blew sky-high! This was the first of many lucky events that enabled me to come home later.

Lt. George Olsen and I were taken to the headquarters of the 158th Field Artillery Battalion of the 45th Infantry Division where we reported for duty. As we walked into the command post (CP) we could hear a desperate report coming in over the radio from one of the FOs (forward observers) up with an infantry company. He was in a building and we could hear the Germans breaking into the house and shooting him! There were several lieutenants in the CP, along with Captain Beverly Finkle and Lieutenant Colonel Dwight Funk, the battalion commander. These lieutenants immediately started dividing up some of the valuables that had been collected by the officer who had just been shot. Then they looked at what Olsen and I had brought with us, and started dividing up the things we had---what a nice welcome! Both George and I were assigned as Forward Observers to C Battery, which normally fired in support of the 3rd Infantry Battalion of the 157th Infantry Regiment. As FOs, we would usually work with the three “line companies” (Companies I, K, or L) of the 3rd Battalion. Our mission was to call for and direct artillery fire on targets ahead of them. Along with our assignments, we received the news that the life expectancy of a forward observer was about six weeks. It seemed that our destiny for the future was to be killed, wounded, or captured, or any combination of these. What a future with my first real job after graduation from college!! Olsen and I were each given a jeep and driver, a “710” radio, a radio operator and two men to carry the radio and batteries when we dismounted from the jeep. Our men were also replacements, but had been there for some time and were already settled in with other jobs in and with C Battery. Now, when not up with the infantry as part of our FO party, they would continue living with the firing battery. Due to the small size of the Anzio beachhead, Olsen and I would billet ourselves with Service Battery instead of with C Battery to help relieve some of the congestion around the firing battery while we were on the Anzio beachhead. The first job that Olsen and I had was to dig a hole to stay in and to get situated. Everybody lived in dug out holes, which were covered with earth for protection against the German butterfly bombs, with which the German Air Force repeatedly attacked the beachhead. These bombs, each weighing 4.4 lb. were packed inside canisters, which opened after being dropped, scattering the bombs over wide areas. When the bombs were ejected from the canister, small wings deployed, which stabilized and slowed the bomb and also set the fuse. The bombs could be set to explode on contact with the ground or as an airburst. Over time, the fragments from the thousands of butterfly bombs dropped at Anzio damaged or destroyed just about everything above ground. We dug a hole about eight feet square and about 6 feet deep with a dog leg entrance. We went into Anzio (town) and got doors and other timbers etc. to cover our hole, making sure the cover was strong enough to support at least two feet of dirt on top of it. We had a bulldozer from Service Battery dig holes for our jeeps so the tires wouldn’t get hit by the steel bomb fragments. Then we ran a wire from a jeep over to our hole and hooked up a light in our hole. All the comforts of home! The toilet was out in an open area where there was a shovel with a roll of toilet paper so each person could dig and cover up his daily contribution to build up the fertility of Mussolini’s soil. Then it was about time for us to get to work doing what we came to do. My FO party consisted of Dick Borthwick as my radio operator, Charles Smith could also operated the radio, but his and Herman Rodriguez’ main jobs were to carry the “710” radio and batteries. Carter was my driver for the jeep. Olsen had a similar crew. To begin with, Sgt. Walt Schumaker, who was an original “Thunderbird”, having been in the Oklahoma National Guard when the Division was called to Federal Service. He had been through Sicily and Italy before Anzio and had been out with a number of other Forward Observers and was well acquainted with how things were done in combat. He helped me get acquainted with their method of calling for and adjusting the artillery fire. Needless to say this was a lot different procedure than they taught us at Ft. Sill. It was much more practical and easier. After a couple times up with Walt’s help, I was on my own from then on. At Anzio I had a lot of interesting events that happened and will try to relate a few of them to help the reader better understand what life was like in what had been described as Germany’s largest concentration camp—the Anzio Beachhead. One night I went up to relieve another FO at an outpost. Before he departed, he showed me a piece of shrapnel that had landed by his feet. It had his initials on it! (German ordnance and other military items were marked with a three-letter code, such as ”cda” or “fzo” to identify the manufacturer. Apparently the shell fragment that had landed at his feet had a manufacturer’s code that was the same as his initials.) Right in front of us was a barbed wire entanglement between us and the German’s front line. I was told that we had received an intelligence report that the Germans were expected to drop paratroopers that night. Naturally we all were extra alert. Along in the night we heard a big commotion in the barbed wire in front of us. I directed some artillery fire in and behind the barbed wire and the Infantry shot it up good with their machine guns and other weapons. Then all was quiet again. In the morning we saw a dead cow that had got tangled up in the barbed wire out in front, instead of what we thought were German paratroopers. Being in a defensive position, we had telephone wires to the various units instead of depending entirely on radios. However, the Germans soon found our telephone wires and tapped into them and we tapped into theirs. Over the telephone we enjoyed listening to “George and Sally” on the German radio propaganda programs that were designed to make the Americans and British homesick by playing all the current popular songs. Either we had to check our wires quite often or use radio for official calls. The Germans also dropped the propaganda leaflets to help destroy our morale. At least that was their intended purpose, but we found them quite amusing. On March 4th I had a close call. I was back at the firing battery (Battery C) and they were getting a lot of counter battery fire, i.e., the German artillery shooting at our artillery positions. I had gone from the Command Post (CP) to the kitchen truck to get a can of C rations for lunch and was on my way back to the CP when a German artillery shell just missed my head and landed about six feet on the left side of me. I was lucky that most of the fragments went out away from me and all I got was a few small pieces of iron and lot of sand etc. embedded in my skin—along with a bleeding and broken left eardrum. Back at the CP it took a couple of people with tweezers, two or three hours to pick all the stuff out of me. Lady Luck had smiled on me again. The British were on our left flank and back at Service Battery we were fairly close to some of them. After getting acquainted, we visited back and forth. We didn’t get a liquor ration and they did, so one evening they invited Olsen and me over to drink and visit. Their hole lived up to their motto - “As long as you have to go, you just as well go first class”. They had dug a hole about 10 feet deep and had about four feet of dirt over the top of it. . Also electric lights like we had, powered from a near by vehicle. While sitting down there, we heard a loud thud up above and dirt started shaking down on us. We went outside to see what happened. On top of the hole lay a huge projectile from the big (280mm) railroad gun that the Germans had up near Rome - the “Anzio Annie”, as we called it. It had apparently hit a tree that deflected its trajectory so it landed on its side without hitting the fuse on the end of it, which would have caused it to explode. Had it exploded, it would have made a hole big enough to bury a truck in. Lady luck smiled on me again! There had been quite a few trees around the Service Battery area so when a German ME109 fighter plane was shot down close by some of the enterprising soldiers took the machine guns out and mounted them on about a four-foot stump of a tree they had cut off. By late spring there were at least six or eight of these mounted and used every time a German plane came near. I don’t know whether they ever shot down a plane, but they had fun trying. One evening the Germans hit a large ammo dump about a mile from Service Battery. The resulting explosions would put all the 4th of July fireworks displays I’ve seen to shame. For about an hour and a half it literally rained red-hot pieces of steel all over the area. Lt. Colonel Funk had Service Battery build a still to take the alcohol out of the Italian cognac and Vino that the GI’s liberated. Otherwise it was about like drinking gasoline and very likely could have been detrimental to the health of the men. They had the kitchen order lots of orange juice, pineapple juice, etc. to mix with it. This was then distributed to the men in the firing batteries. This was just another example of Colonel Funk’s dedication to the welfare of the men in his Battalion. On Easter Sunday I was

up with the Infantry in their trenches next to no-man’s land. The

Germans were on the other side of it, about 300 feet away.

A rather unusual thing happened. The Germans were not shooting at

us, and they were acting a little strange in that they were crawling

back and forth to men in other trenches or holes. Before we knew what

they were doing, we shot several of them with rifles. After capturing

one or two, they told us what was happening and we quit shooting them.

Because it was Easter Sunday, they were given a liquor ration and orders

not to shoot at us. The men closest to us were mostly Polish or other

nationalities the Germans had taken as prisoners and forced to fight us.

In fact some of them still had on their original uniforms instead of the

German uniform. Behind these frontline men were the German non-coms,

whom the front line men were more afraid of than they were of us. If

they retreated from us they would be shot by the non-coms. Behind the

non-coms were the German officers, so the non-coms didn’t dare retreat

either. After that we aimed

for the ones behind the front lines. To punish these front line men, the

Germans had sometimes sat in their holes and gave the men close order

drill, hoping we would shoot them.

In April it was warm and sunny-absolutely beautiful weather—but we didn’t get to enjoy it much, as the fighting went on without let up. One night when the moon was not shining, I went up with the Infantry where I relieved another FO. I only took two men of my FO party with me-Dick Borthwick and a new man, Homer Smith, who had been an infantryman in the 180th regiment and had gone AWOL to come over and join our artillery outfit. We, and some of the infantry men, occupied a house that was nearly surrounded by the Germans; it was sort of like being out on the small end of a piece of pie jutting into the German lines. The enemy was all around us, and even occupied a neighboring house next to us. We could only get to or out of our house in the black of night or there was a high risk of getting shot. Even after we got into the house safely, it proved to be a dangerous place, as the Germans shot at us from the neighboring house every time we moved by a window Just outside one of the windows were two dead Germans that had probably been there for two weeks. With the warm weather they swelled up and really stunk! In addition, there were about 40 head of cows close by that had been killed by artillery fire a couple weeks before and they, too, were really stinking. As if we didn’t already have enough to worry about, one day one of the infantry soldiers went nuts. He was subdued only when a GI put a hammerlock on him. We had to take turns holding the man in that way all day and part of the night before he could be safely evacuated. One day I was directing the fire of one artillery gun around the house next to us. One shell landed out about 30 feet north of this house and I saw the legs and arms of a man fly up when the shell hit what was apparently the hole that one of their observers was in to watch us. From there he could relay the information to those in the house. Anyway I was glad to get him. The replacement for the soldier, who had gone nuts and had been evacuated, came up during one of the nighttime re-supply patrols. He had been wounded and had just returned from the hospital. He had a big stack of letters that had accumulated while he was gone, and at daylight he got up to start reading them. That’s when the Germans decided to make another effort to destroy our house. One of the first shells the Germans shot at us made a direct hit on this man and killed him as he was sitting in a doorway where he could get more light to read. The house we were in was a big square house made with thick stonewalls and stone interior partitions. As the Germans continued shooting at our house with either a big mortar or 88, or both, Dick Homer, and I knocked a hole in the concrete floor and dug back under the big stone stove that was in the interior corner of the room. We finally got a big enough hole under it for the three of us to get in to protect us from the explosions and fragments of the incoming shells, the falling masonry, and the collapsing roof. I counted the shells as they exploded, and there were about 160 shells fired at our house that day, one at a time, rather than in salvos. Over 80 of them direct hits on our house. After the roof was knocked in, the shells landed and exploded in the room with us. The concussion was terrible as were the fumes and smoke from the shells. When it got dark, the

Germans stopped shooting at us. Fortunately, there was no moon so we

were able to get out of the house early that night, and made our way

back to our lines. The week we had spent in the stone house had been a

very draining experience. I had gone seven days and six nights without

any sleep. We didn’t dare go to sleep as the Germans could have come

and killed us all before we knew what was happening. The shelling on the

last day, however had been the roughest on us. Although Homer had been

in the middle when we huddled under the stove, he suffered the worst

effects of the shelling. The

concussion had torn all his insides loose, and he died from it. Dick and

I survived, but with very sore lungs for a week or two. Later I

attributed my two episodes

Sometimes the Germans were using wooden bullets in their rifles. These were not very accurate but if they hit a man, they would penetrate and splinter up. As they couldn’t be detected by x-rays, they started an infection and the person would die, but with a very painful death. Therefore we inspected the rifles of all captured German soldiers and killed them if they were using wooden bullets. On May 22 I had my first airplane ride. They took me up in a Piper Cub liaison plane to look over the area we would be attacking the next day. Ordinarily the Germans didn’t shoot at these planes, as the pilot could see where the shooting came from, and would direct our artillery fire on them if they did. He could see where the shooting came from. However, on this occasion we must have gotten too close, as they started shooting at us before we could turn and get away. It was a very helpless feeling, being up there in an unarmed and unarmored, slow moving light airplane while the Germans shot at us. It seemed like we were sitting still while they were shooting at us. I was glad to get back with my feet on the ground again. The next morning the breakout from the beachhead began. We got up early and went with the Infantry to our position to start the attack. Getting ready and waiting for H Hour (the time to shove off on our attack) was the worst part - anticipating what will, or what might happen, and wondering which of us will get killed or wounded before night. To add to our discomfort, it rained a little to make us cold and shivering as we waited to push off. At H hour, 6:30 am, every artillery piece on the beachhead (640 guns) started continuous firing right in front of us. There wasn’t any place larger than 10 feet square that wasn’t hit by at least one shell. After the artillery pulverized the German positions awhile, we moved out in the attack. The first thing we encountered was a German minefield. I was following one of the platoon leaders and was close behind him when he stepped on a mine, which blew off one of his feet. I took his platoon on through. We had just gotten past the minefield when the platoon leader of the following platoon stepped on a mine, so I went back and led his platoon through. Luckily I didn’t step on one. Most of the Germans were still in their holes and either too scared to come out or too shocked from all the artillery fired on them to offer much resistance. We hollered at them to come out and if they didn’t immediately comply, we threw hand grenades in and went on to the next holes. As we advanced we radioed back and lifted the artillery barrage so that it stayed ahead of us-a rolling barrage. By about noon we had gotten ahead of the units on either side of us, so we stopped just over the top of a long hill and occupied some of the shallow German trenches while we waited for them to catch up. holding the headband in. This little clip was bent almost double where the piece of steel had hit it. It did fracture my skull as it hit just in front of and at about at the top of my right ear. If I had had my head turned an eighth of an inch either way it would have missed this little clip and killed me instantly. Once again Lady Luck had a big smile on her face.

About an hour later after I had recovered somewhat from the concussion and the initial shock from the near-miss of the 88 shell, six German Mark VI tanks started up the hill toward us. When the closest one was about a block and a half away, he spotted us. In my mind’s eye I can still see him lowering his 88 down. The first three shells he fired missed me by about a foot or so directly above me. I could feel the heat from them as they went by. Then he lowered it down a little and nearly buried us with the next three shots fired. All the time the tanks were advancing and shooting at us, I had been trying to get some phosphorous artillery shells on them. Finally it came. I got two tanks and I think the others pulled back, but we didn’t stick around there any longer to find out. I didn’t know what the next move for the Germans would be, but it was clear that we were in an exposed position well ahead of our flanking units, and just staying there didn’t appear to be a good option. Also, I wasn’t in very good condition from the head injury and all the recent excitement and we were in a hurry to get back over the hill and away from them. I shot out my radio, as it was too big and heavy to carry and didn’t want to leave it so the Germans could use it. I had emptied my carbine on it to completely destroy it and didn’t take time to reload before we left. As we came up to the top of the hill, I looked up to see a German standing at an intersection to the trench we were in. My gun was empty! I looked at him and he looked at me. Neither of us bothered the other and we kept on going. I’ll never know why he was there or where he came from, but he must have been lost, or like I was, too dazed to do anything. We kept on going back, looking for an Aid Station or medics. We followed one of Mussolini’s big drain ditches where there were lots of dead and badly wounded men, both German and Americans. The little stream of water from the previous night’s rain was red with blood. Eventually, somehow, I ended up in a hospital tent that was so crowded I had to sleep on a cot with another wounded soldier. The next day the medics took us to the Anzio harbor and loaded us up on a hospital ship. What a wonderful feeling it was to be on this clean white hospital ship with lights on at night and a bed with clean sheets to sleep in—away from the war. We went to Naples where I spent two or three weeks in the 45th General Hospital. The doctors looked at my helmet, and looked at me, and marveled at the fact that I was still alive. Lady Luck had smiled on me again! (I felt luckier than ever after seeing how badly some of the other soldiers were wounded. The fellow in the bed next to me had been hit in the back with shrapnel and kept begging the doctors to let him die.)

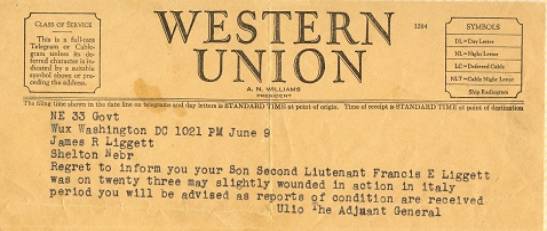

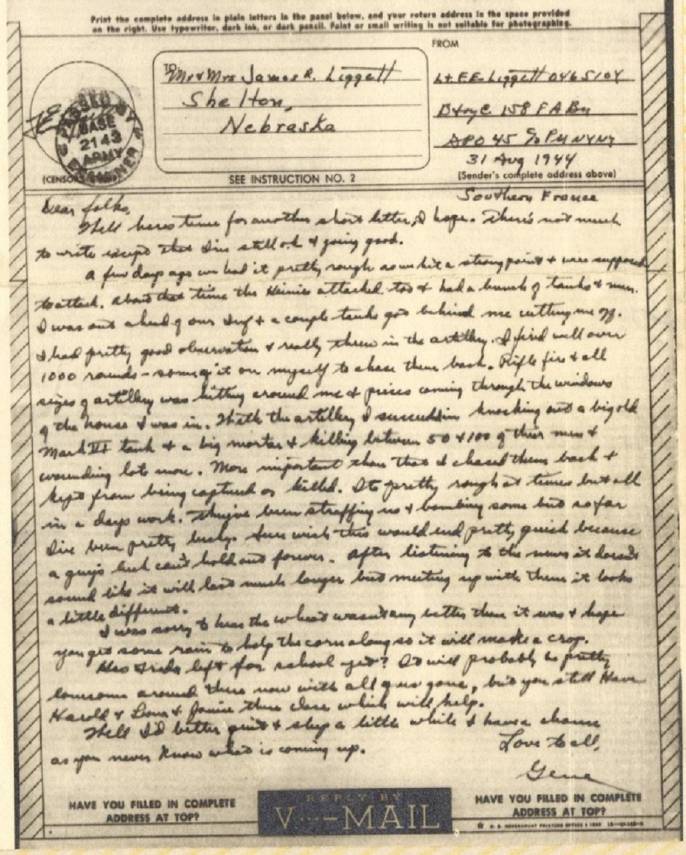

Telegram to my parents Finally, about the second or third week of June, I was discharged from the hospital and along with Frank Mathers, a 157th Infantry lieutenant, and others, boarded a ship and went to Civitevetchi, on the coast just north of Rome. While on this ship, German planes come over to bomb and strafe us and again I wished I were back on land where I could dig a hole to get in. It was a helpless feeling sitting out there in the bay, with enemy planes coming at us. Fortunately, this time we did not get hit. After getting off the ship we were met by a 45th Division truck and were taken to the Division bivouac area. (While I was in the hospital, the 45th Division had advanced on to Rome and a little farther, before they were relieved and taken out of the line.) On the way we passed right by and saw the big railroad guns the Germans had been shooting at us while we were on the beachhead at Anzio. These huge guns were on a railroad track and when not firing they were pulled back into tunnels for protection. (Later, one of these two “Anzio Anne” guns - the one named “Leopold”—was taken to Aberdeen Proving Grounds, in Maryland, where it is still on display at the US Army Ordnance Museum.) After getting back to the 158th FA I got together again with Dick Borthwick, Charlie Smith and Herman Rodriguez. For the next three days my men went sightseeing with other Battery C men. With my jeep and Carter driving, Lt. George Olsen and a Lt. Grabowski, and I went sightseeing in Rome. (Carter had the uncanny ability to never get lost and to always be able to get back from wherever we were.) We went to the Vatican and St. Peter’s, but not being a Catholic at the time, I didn’t understand the full significance of all there was to see. Of course, the Swiss guards at the entrance were quite impressive. All the paintings and mosaic pictures were very interesting, but I was surprised that there were no seats or pews to sit down. I thought it odd that everyone had to remain standing. We also went down in the catacombs and I remember the sort of shelf with St. Cecilia’s body on it. It never decomposed; she was lying there as if still alive. We didn’t see the Pope, but there were lots of Cardinals, Bishops, and Priests and other religious figures to be seen, and lots of visiting GI’s, too. Another place we visited was the old Coliseum. It was easy to visualize what it had looked like so many centuries before when the Romans used it for their amusement by watching all kinds of fights to the death by both men and animals. We saw the balcony where Mussolini made many big speeches - lots of old statues all over Rome - other churches and many government buildings. The streets were crooked and very narrow, making driving or walking difficult or hazardous. One day we went to the big Rome Opera House where Irving Berlin and others with the USO show were entertaining the American and British soldiers who had fought so long and hard to get there. It was a beautiful building. In Rome the general population was somewhat different than those down in the southern part of Italy or Sicily. Here most were bigger people, more blondes and blue-eyed people, where in the south they were smaller, with dark hair and dark eyes. While I very much enjoyed my time in Rome, the visit had to be a short one, since the division was preparing to move. After three days of sightseeing, the division’s vehicles were all lined up in convoy formation for the long drive to our new bivouac area near Salerno, south of Naples. Though we didn’t know it officially, we were being assembled to prepare for the invasion of southern France, which was to take place in August. At Salerno we recuperated from the long fighting at Anzio, replaced those men who had become casualties, and began training for the invasion. Amphibious training was part of the schedule, so it was clear to us that another landing was to be in our near future. Numerous times we practiced climbing down the rope ladder-like nets on the side of ships into small landing craft below. We also spent a lot of time riding around in the landing crafts, as we would do later when we landed on the beaches in southern France. The old-timers in the Division well remembered the bloody battle at Salerno nearly a year earlier, when our forces assaulted the Italian mainland - and this was after having taken Sicily. After our move, Olsen, Grabowski, and I lived in a tent in an Italian orchard. The weather was warm and we enjoyed not having to fight for a while. A couple times we went to Pompeii and it was very interesting to see the way people lived about 2000 years before. They died when Mt. Vesuvius, the volcano, erupted and covered them up with hot ash. While here I got to go on R&R (Rest and Recuperation leave) to Sorrento and stayed in a hotel taken over by the Army. It was a well-deserved week of vacation and relaxation. I went to the famous Isle of Capri one day, and spent some time swimming in the blue Mediterranean. It was here that I lost my high school class ring as it came off while swimming. One nice afternoon, back in the orchard, I stayed in our tent to write some letters while Olsen and Gabby went someplace. While I was sitting there alone, a garter snake about two feet long came across the ground floor in our tent. I grabbed him by the tail and with a quick movement like cracking a whip; I broke the snake’s neck without popping its head off. I coiled the dead snake up on Grabowski’s pillow. That night when Gabby came home - drunk as usual - he saw the snake, pulled out his .45 caliber pistol, and emptied it on the snake while I pretended to be asleep—until then. Grabowski was one of the few people who had an air mattress in his sleeping bag. Needless to say, his air mattress was well ventilated. He always thought the snake was alive when he shot it and I never told him otherwise. By the second week of August all the equipment was loaded on the ships and on August 13th we headed out to sea. After the ships were organized into convoy formation, we sailed west, going between Corsica and Sardinia. I never minded riding on the Navy’s ships, as we officers were always given nice beds and had good meals with the navy officers. The trip was uneventful. Early on the morning of August 15 we ate breakfast and put on our backpacks and prepared to leave the ship. My FO party embarked in a landing craft with Lt. Van Barfoot’s infantry platoon of I Company, 157th Infantry Regiment. With a full pack on our back and carrying our guns, we climbed over the side and down the nets to the small landing craft below. The water was sort of rough with large swells. That made it difficult and dangerous going from the more stable big ship with the nets to the small boat that was bobbing up and down far below. We were two or three miles from shore when we got into the landing craft and it seemed like we traveled awfully slow toward the shore. Massive firepower was applied to the beaches, even before we got into the landing craft. The Air Force had bombed the beaches and the area immediately behind them. Then the Navy fired their big guns at previously known targets. All the while we were headed toward the beach, the navy fired small rockets over our heads. Some of them were defective and landed in the water near us, but again we didn’t get hit - just scared. When we got close to the beaches the offshore fire support ceased. Now it was up to us. With me and my FO party was a navy officer who was supposed to direct the fire from the ships after we landed, and until our artillery got on shore. Then I would take over. We knew there was a sea wall where we were supposed to land at St. Maxime so we took along some dynamite to blow a hole in it to get off the shore and on to the beach. We also took some ladders in, just in case we needed them. The dynamite had got wet and wouldn’t explode so we set up the ladders. Lt. Barfoot climbed up and sat there for a few seconds and looked back and said “Come on, they didn’t shoot me!” The Navy and Air Force had done a good job of getting rid of most of the Germans in our sector, so we had little trouble getting into St. Maxime. Once in the town, however, we encountered numerous snipers who had to be cleared out of houses, buildings, and other structures. The Navy officer with me was shot by a sniper. I don’t think he was killed though as we left him to be taken care of by the medics. Now I had the job of directing fire for the naval gunfire support too. With our artillery fire direction center personnel working directly with the naval fire direction center, I could use my 710 radio to communicate with them and direct the adjustment of the shells in my usual manner. They would convert this to the navy’s method of directing their gunfire. After securing the town, we turned to clear out the German positions along the coast where we soon encountered a high hill with Germans in deep holes and tunnels. We went around the backside of it and I directed the fire from the battleship “Texas” and several Destroyers. Since we were directly in line with the ships and the hill, if any of the shells would have come over the top of the hill we would have been hit. So instead of using the standard practice of adjusting fire by using the first two shells fired to get the target bracketed, I was real careful to creep up on the other side of the hill with one gun to get to the top. Then I called for “Fire for effect” and all the guns assigned to this fire mission fired on the target at once. With those big 14-inch shells, the hill shook and sort of settled down. It was a lot different than shooting the 105’s of our artillery. There were still a lot of Germans in holes on and around the hill despite the heavy shelling. So after the Navy stopped firing, Lt. Barfoot and his men moved up. The hill had a barbed wire entanglement around the upper part of it, so with a bangalore torpedo, the infantry opened up a gap in the wire to go through. Lt. Barfoot had gotten rid of his gas mask and filled the bag with rifle grenades that were his favorites. He went in alone and it reminded me of shooting prairie dogs in Nebraska. One would pop up out of a hole and Van would shoot him. Then another, and another, until he had killed seven or eight of them. Then all of the platoon went in and finished the job. A German captain, a sergeant, and one or two others surrendered. I helped search them and I took a really neat safety razor from the captain. The sergeant was a mean looking guy and he had a pair of brass knuckles in his hip pocket. One of the Infantrymen took it and tried it out on the German to show him how it felt. (That is why we had been advised to never carry a big knife.) That night we were tired and I slept outside on the sidewalk by a house that had been destroyed. From then on we walked and cleared the retreating Germans who would stop and fight and then we would chase them again. Lots of times they would fight almost to the last man for some important road intersection or some other key piece of terrain that could be defended. Our artillery had a hard time keeping up and having the guns in position to fire at all times. On one of these occasions my driver, Carter, had done some trading with the French people and we started cooking a rabbit stew that included some potatoes and carrots. We had just got started with the cooking when we had to pack it up and move. Again we got it all out and started cooking again, but before it got done, we had to move again. The third time we finally got it cooked so we could eat it. During these fast moving situations I usually had Carter bring my jeep so we could ride instead of walking until we engaged the enemy again. Otherwise he stayed with C Battery until we needed him. As we went farther north, generally following the Rhone River, we got into areas where there were lots of good ripe tomatoes and then into the grape vineyards with lots of delicious ripe grapes. They were welcome supplements to our C or K rations. The French civilians were very glad to see us come and always gave us a big welcome. They dug down in the dirt floors of their cellars and got some of the best wine they had buried to hide it from the Germans. Since the Germans had taken all their livestock and most everything else they could, these people had been hurting for food. Our chocolate bars (D-bars) were some of the things they hadn’t seen for several years. The Germans had thousands of troops back inside France, and we in the Seventh Army pushed north up the Rhone Valley, while Patton’s Third Army was pushing eastward from the Normandy beachhead. A large German army was at risk of being trapped behind the two American armies. The tighter we closed this gap, the harder the German rearguard fought so their main body could escape back into Germany. Here was where we had some real hard fighting. Our American OSS (Office of Strategic Services) officers had been helping to organize resistance groups with the FFI (Free French of the Interior) as well as the Marquis (the Communist French) to fight the Germans. Arms, ammunition, explosives, etc. were dropped to help these Resistance Fighters to sabotage and otherwise harass the Germans. Occasionally we would overrun an area that they worked in and an OSS officer would join us for a while. Some of the French also worked with us as they could contact the local residents who knew the land and could move through the German lines with relative ease and were able to monitor and report on German activities ahead of us. Many times we just took the main towns and bypassed some of the smaller ones to the sides as the Germans seldom stayed back where they would be trapped. One day a young lady came running over to us and was so hysterical she could hardly talk. Finally somebody understood French and could make out what her problem was. We had bypassed a small village over three or four miles to the side of us where the civilian FFI had been supplied rifles and ammo. They got real brave since we were close, and chased the Germans out of the town. Then they ran out of ammunition and the Germans came back. They tied the French men up and put a stick of dynamite in their mouths with a long fuse so the individual could watch the fuse burn until it blew his head off. The women and kids were treated even worse. Their eyes were poked out and their fingers chopped off. Since no artillery was thought needed, I didn’t go over there. However, few prisoners were taken in this case. This was a good example of what the Germans were capable of doing to other people they controlled. One night my FO party and I were waiting beside the road under some bushes for our Infantry to meet us before crossing the Daubs River. The Engineers were finishing building a pontoon bridge across the river. As we were sitting there under some trees and bushes, four trucks loaded with Germans came up the road and stopped right in front of us. My initial thought was to open fire on them, but after a moment’s hesitation, I came to realize that there was no way the four of us with Carbines could kill or capture all those Germans. I decided that I would rather be a live coward than a dead hero. So we sat there watching them. After a few minutes they drove on across the pontoon bridge. They were the first ones to cross it after our Engineers built it. Maybe the Engineers saw them and felt the same way I had - or they didn’t recognize the fact that they were Germans instead of Americans. Later, our infantry arrived and we all went across. One day we were supposed to attack and while we were waiting to push off, the Germans decided to attack us. They started out with a lot of artillery firing on us while we were getting lined up. It is nerve wracking waiting for the next shell to land—wondering where it will hit and who will be the victims. Finally we pushed off too - with me directing our artillery fire on them ahead of us—with them trying to do the same to us. We finally made some progress, and my FO party and I got in an old stone house, from which I had good observation of the enemy from a window. The Germans were circling around from one side trying to get us surrounded. I fired over 1,000 rounds at them and finally succeeded in chasing the Germans out of the trees, forcing them to retreat across an open area. I had already adjusted on this area and had established a Concentration Number for it, so once the Germans were out in this open area, all I had to do was call for this concentration number and the whole battalion of our artillery would immediately blast the area. Then I could shift back to the trees to chase out another bunch. I killed at least 100 or more of them, and no doubt wounded three or four times that many more. However, just when things were going pretty well for us, several Mark VI tanks and supporting infantry, attacked toward my house. While I was looking out of the window and adjusting fire on the Germans, I was hit in the forehead by a fragment from a shell that exploded nearby. Again, my helmet saved me as it just made a big dent in the steel helmet but didn’t come through. Lady Luck had smiled on me again, but I wondered how much longer this could go on. The Germans pressed the attack despite the artillery fire, and it looked like they were going to get through to us, so I took a chance and brought the whole battalion of our artillery in on our position. While it was hitting all around us, my men and I ran out and got away from them without getting hit. The Germans had sense enough to keep their heads down while the artillery was coming in. Lady Luck was still smiling, as my men and I got away without being killed or captured or wounded that day.

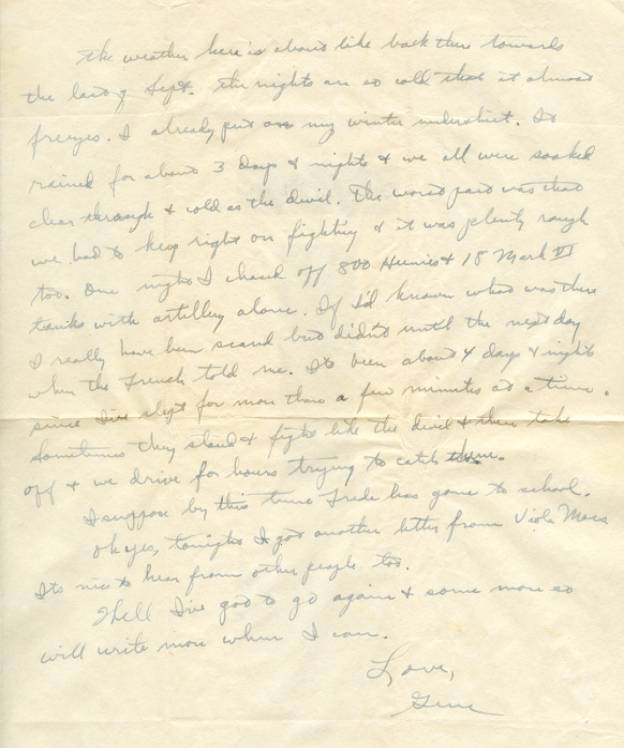

After a few more days of minor skirmishes with the Germans, we had advanced to the edge of the Alps, and were getting fairly close to Switzerland. The land was characterized by long sloping hills with most of the higher area forested. The ground on about the lower third of the hills was cleared and provided grass for livestock. Usually in the bottom was a little stream and an occasional village or town - very picturesque. While back at the battalion headquarters, preparing to return to I Company again, I jokingly told Col. Funk that I was going over to Switzerland and they could go ahead and fight the war without me. I was never to see the Col. again, but I never got to Switzerland either. On the night of September 10, 1944, I was with Lt. Van Barfoot and his platoon of I Company. We knew the Germans were up ahead of us, but we didn’t know where. Leaving my FO party and Van’s platoon behind, he and I took a sound-powered telephone and strung a wire as we went. In the middle of the blackest, darkest night imaginable, the two of us moved cautiously through the forest to see where the Germans were. Every little twig we stepped on sounded like a herd of elephants out there. Once we saw a small luminous spot ahead and Van raised his gun to shoot, thinking it was a man’s wristwatch - and it did look like it could be. However, I had seen this type of thing before and thought it was probably some free phosphorous from an old dead and decaying tree. Luckily, I grabbed his arm and stopped him before he shot. Going up toward it, it did turn out to be phosphorous, so we avoided alerting the Germans by shooting at the tree. We kept going until we came to the edge of the clearing and though we still hadn’t encountered any Germans, we waited there until it started getting light. Down the hill and about 500 yards from us was the little town of Abbenans. There was the usual cleared area below us with a stream in the bottom. There was also a road with a bridge that crossed the stream and led into the town. We could see a lot of Germans in the town so, using the sound-powered telephone, I started firing artillery on them. All the houses had red tile roofs and the artillery shells hitting them sent up a cloud of red dust. One Frenchmen came out waving a sheet indicating he didn’t want us to shoot up his house, and I really couldn’t blame him. After firing around and on the town for an hour or two, suddenly about 60 to 70 ambulances left the town. We had our doubts that they were all carrying wounded people but we didn’t shoot at them. About that time a tree that was right out in front of us, only about 200 feet away started moving. It was a well camouflaged anti tank gun with a five-man crew. They pushed it down the hill and, as they were crossing the bridge, I got a direct hit on them. They flew in all directions. The bridge was also pretty well demolished. At about noon we didn’t see any more German activity in Abbenans so we called my FO party and the platoon of infantry to come and join us as we went into town. There were no more Germans there. Lt. Barfoot’s platoon was then relieved and they went back in the company’s reserve. After having been with Barfoot’s platoon most of the time since we landed in France, this was the last time I was to see him until many years after the war.. A few weeks later Lt. Van Barfoot was awarded the Medal of Honor for extraordinary heroism while at Anzio and was sent back to the States to receive it from President Roosevelt. He was a remarkable individual and excellent soldier. Van was half Choctaw Indian and about 6 ft. 6” tall. He would rather go prowling around at night behind the German lines than stay back on our side. My FO party moved out with the rest of I Company and headed out across the clearing on the other side of Abbenans and up the slope toward the wooded area at the top. Some of the Germans who had withdrawn from the town had taken up positions in the woods above us where we couldn’t see them, and were firing down on us. As we advanced up the hill, I walked along beside the company commander, Frank Mather, whom I had known since we were both patients at the same time in the hospital in Naples. He always carried a pistol instead of a rifle. I always carried a carbine. I remarked to him that someday he would be identified as an officer because he carried only a pistol and might get shot by a sniper. It wasn’t 15 minutes later that, as we walked side-by-side talking to each other, he stopped right in the middle of a word. I looked over at him as he fell to the ground. He was dead - having been shot by a sniper from the trees above. The rest of us kept going and late in the afternoon we got to the top of the hill. Lt. Howard Litske’s platoon was supposed to be out ahead of us. I joined the battalion commander, Major Merle Mitchell, who had come up to temporarily take command of I Company since Lt. Frank Mather was killed. Other officers with him were Captain Henry Huggins, and another Lt. and a Frenchman. With them, we looked at our maps and tried to find a road that went down on the other side of the hill, but couldn’t find it. After deciding what to do, I left Major Mitchell and the other officers all standing in a group, and started walking back to my FO party. About 10 or 15 seconds later, I had gone only 50 to 75 feet when the Germans opened up with a machine gun, firing in our direction. I assumed that Major Mitchell and all the other officers who were standing there with him were killed because they were not taken as prisoners, and the Germans had occupied the area. Right where I needed it, and when I needed it, there was a shallow depression inside of where the walls of an old building apparently had been. My FO party was already in it when I jumped in with them. The Germans continued firing directly over us while our tanks from behind were shooting back over us at the Germans. I set up the radio and was directing artillery fire in a semi circle in front of us just by the sound, as I didn’t dare stick my head up. As it got nearly dark our tanks pulled back, which was customary, and the Germans quit shooting too. A few minutes later when everything was quiet, we heard a German tank coming toward us real slow and with very little noise. All we could hear was the clank-clank-clank of the track as it came closer. I told my men that it was time we were getting out of there and that I would try. If I made it, they were to follow. NO---NOT YET

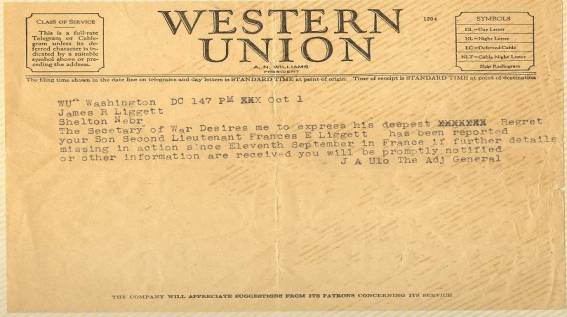

Chapter II I got out and had to go across an open area of about 150 feet to get to the trees beyond the clearing. It was practically dark then. When I got out in the open, they started shooting at me from all across the front of the trees ahead of me as I headed back toward our lines. I raised my hands and gun and hollered at them to stop shooting. They answered back in German! There I was out in front of a whole line of Germans and in the open with no place to go or way to get there. I had no choice except suicide or be captured. They came out after me and took my carbine out of my hands. Believe me, that was a traumatic experience with a feeling of helplessness when they took my gun away from me. A couple of nights before, I had lost my binoculars so borrowed a pair of real good German binoculars from one of the infantrymen. I had them around my neck. Also I had a little German pistol on my belt. If we ever caught a German with any American equipment on him, we killed him, and they normally did the same thing. Having no time to get rid of them, I figured this was going to be the end. However, to my surprise, they acted like a bunch of little kids to see who was going to get them. Later I found out that they were some of the German Luftwaffe ground force that were put up in the infantry and this was their first fighting. Again Lady Luck looked at me and smiled from ear to ear . One of the first things the Germans did was to take my glasses off and stomp on them to break them. After finishing searching me and taking my cigarettes and lighter, money, and jack knife, they made me lay down with my head on a big rock. A rifle was held against it on the topside until they finally captured the rest of my men. Later, Dick Borthwick told me they didn’t know that anything had happened to me, and came out one at a time only to be captured too. None of them were wounded, but the Germans did shoot through the radio while Smith had it on his back. After they got all of us, they fed us some real good beef stew with potatoes, carrots, onions, etc. that they, too were eating. This was probably the best meal I was to get from the Germans while I was a POW. My Lt. bars and insignia were on my shirt collar, but I had them covered so they didn’t find out that I was an officer or I might not have been treated as well. Lt. Howard Litske, a platoon leader, and one of his men were also captured, apparently before I was, as his platoon was supposed to have been out ahead of us,. A German soldier had been shot through the stomach and without a stretcher, the six of us had to carry him about ¾ mile down the hill on a shelter-half, holding it tight so his middle didn’t sag down. Every time we let it sag down, a guard would jab us in the back with his bayonet. The Germans took us down a trail on the back side of this hill to what appeared to be like a Regimental Headquarters. When they had searched me, they had failed to find my map that I had inside my shirt next to my chest. It had our unit’s location etc. on it. As we were going down the hill, I managed to hide it in some bushes next to the trail. At the headquarters we were turned over to an old German Captain. He had learned to speak English while he was a POW of the English in World War I. With an English accent along with his German accent it was rather comical, but he was a pretty good old guy and gave us some good advice on things not to do. Then we were put in a truck and taken to a schoolhouse where we slept on the floor that night. Telegram to my parents:

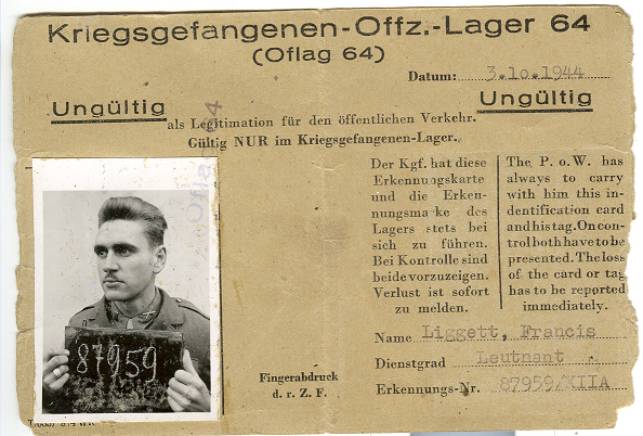

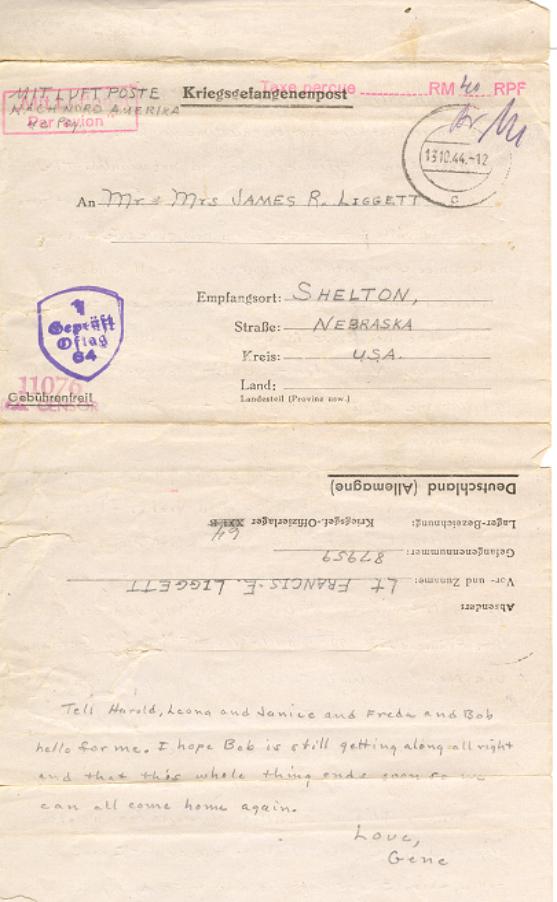

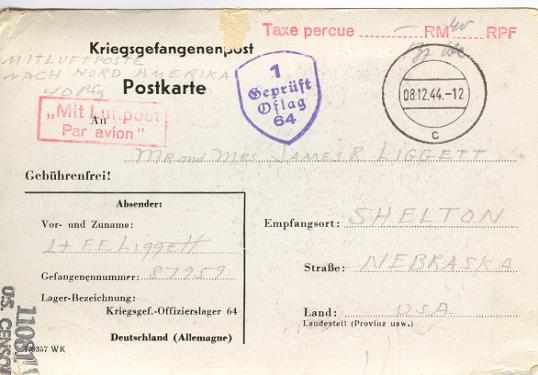

Then he took me to another room where I sat by his desk, while he tried to visit a little. After only giving him my name, rank, and serial number, he picked up a big black book, about 12” by ‘15” in size, and about two or three inches thick. He opened up the book and found my name. He told me where I came from in Nebraska; when I went into the Army; and every place I had been stationed in the States, when I left the States, and every place I had been since going overseas. I was amazed! Obviously they had this same information on thousands of other Americans. (Even today, I don’t know how they got all that information, and much less how they kept it up to date - and without computers. The only explanation I have ever heard was that they had enough people in the U.S. reading newspapers and keeping track of every one in every small town in the U.S. and forwarding the information to Germany somehow.) I had given my name, rank, and serial number, and the officer did not press me for any more information. Thank God they didn’t put me through the bathtub torture. The next day we were taken over to Mulhouse, France, arriving there just in time to be rushed into an air raid shelter during an American bombing attack on the town. When that was over, they put us on a boxcar, We were each given one loaf of German bread to last us until we got to wherever we were going. The train headed north, but of course we didn’t know where we were going. We traveled at night and sat in the railroad stations during the day to avoid being bombed or strafed by our own American pilots. Their favorites were to catch a train going into a tunnel and bombing the other end of it shut so it would pile up the train in the tunnel. Occasionally we could peek through the cracks of the boxcar and knew we were going north up past the Siegfried line as sometimes we were able to see parts of it. Our destination turned out to be Limberg, Germany. They let us out of the boxcars and marched us to our first POW camp, Stalag XII-A, which was a distribution center for POW’s. This was the last time I was to see Dick Bothwick or Charles Smith. Later I got to see Herman Rodriguez. We were registered into the German POW system and with the International Red Cross in Switzerland. They in turn notified our government in Washington D.C. that we were POW’s. The registration process gave us a certain measure of relief, since we were now officially “on the books” as POWs and the Germans had acknowledged responsibility for our care. Until this time there had been no official record that we were in German hands, and they could have denied responsibility for anything that might have happened to us. Each of us was issued a German metal “dog-tag,” which was perforated so it could be broken in two, permitting one part to be left with a body and the other half taken for the records. My POW serial number - 87959 - was stamped on both halves of the tag. We officers were photographed with a card showing our serial number and the picture, which was glued onto the identification card. We were instructed to carry this at all times.

Dog Tags - WW2 - German & American,

also Korean Conflict:

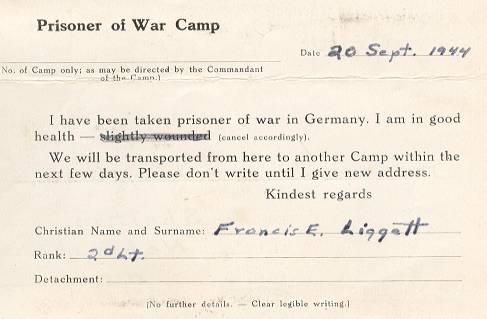

Notification of Prisoner of War Status After several days of processing by the Germans in Stalag XII-A, the officers were loaded into boxcars for another train ride. Again, we were each given one loaf of black bread - which was about one-third sawdust - to last us for the duration of our trip. We had no idea where we were going, but we could tell we were headed east. I remember stopping in Leipzig. Three guards rode in the car with us. They put what looked about like a five-gallon bucket of water in the car for us to drink. The guards told us that after the water was gone, the bucket was also to be our latrine. Most of us had dysentery by then. We had no toilet paper, no way to wash up, and of course no change of clothes, only what we were captured in. One of the guards was an ornery devil and didn’t like us - and we didn’t like him any better. (In looking back, I will have to admit that we probably acted like little kids do, in that they are continually trying different things and testing their parents to see just how much they can get by with and where the limits are.) When the train stopped this one guard supposedly emptied the latrine bucket and refilled it with water to drink without even rinsing it out. However he often left various amounts of the crap in the bucket before refilling it. A person has to be pretty thirsty to drink it, but being the latter part of September with warm weather, and shut up in the box car, we did what we had to do to survive - - no matter how disagreeable. Letter to Parents:

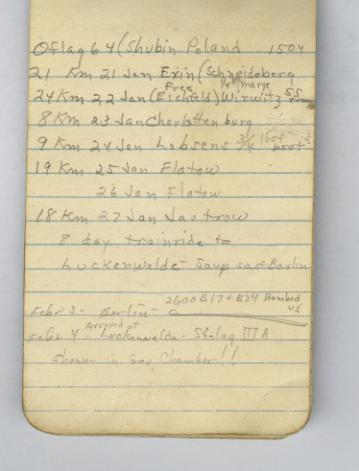

Official Notification of Prisoner of War Status On September 30 our train pulled into the station in Schubin, Poland, and we were ordered out of the boxcar. After a short march we were at our new “home” --- Offizer Lager (Officers Camp) 64, or Oflag 64. This is where all the American ground force officers were kept. (The American Air Force personnel went to separate camps under the control of Herman Goering and the German Luftwaffe.) Our camp was located north west of Warsaw and south of the Baltic Sea - a long way from the American lines. There was virtually no chances of escaping and getting back to our lines. At the time I arrived, there were about 350 American officers there. Most of them had been captured earlier in North Africa or in Sicily or at Anzio. Oflag 64 had initially been a boy’s school before being converted into a POW camp. Then it was used to house POWs of other nationalities before being designated as the primary camp for American ground force officers. It was said that Stalin’s own son, who was a pilot and was captured after being shot down, was held here for a while and Hitler had tried to trade him to Stalin for a German General that had been captured by the Russians. However, Stalin had no use for any prisoner as he thought they should all die fighting instead of surrendering - even his own son, who ultimately died from mistreatment in another German camp.

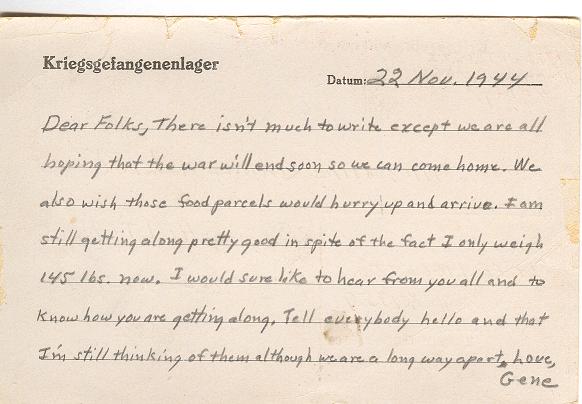

In our barracks we had wooden bunk beds with one above the other. These were placed end to end from the center aisle to the wall. By leaving a space between rows, this formed sort of an enclosure or room. With me, in our little cubicle was Edward (Bud) Fairchild, Dr. Edward McGee, Dr. Monahan, Bill Boucher, John (Tex) Williams, Orville Simmons, and Bill Pryor. Boucher was an Artillery Liaison pilot with the Third Division and had been shot down and wounded. He and I had come up from Southern France while the others were some of the early ones from the Normandy invasion. They were all infantrymen except for the two doctors. Our armies from the south and those from the north had not closed together yet when I was captured. Dr. Monahan got sick and was taken out and we never saw him again. Dr. McGee was later transferred to some other POW camp as a doctor to help other POW’s - even though they had very little to work with except giving advice. In the German army, rank was highly respected and some of it was carried over to showing some respect to us as officers. As such, they had brought in a number of American Enlisted GI’s as our orderlies - mainly to do the cooking and kitchen work. They had their own separate living quarters. Until just before my arrival at Oflag 64, Red Cross food parcels had been issued fairly regularly and the POWs had been receiving letter mail and packages from home. Supplementing the German “rations” with the contents of the Red Cross food parcels and packages from their families had allowed most of the POWs to get along pretty well. By the time I got there, however, the Allies were closing in on the Germans on all fronts and things had taken a turn for the worse for the POWs. Allied bombers, and even fighters, had begun a campaign against the German transportation systems that would continue until the end of the war. Railroad lines, marshalling yards, rail and road bridges, tunnels, individual trains and convoys and even lone vehicles were singled out for continuous attack. Consequently, the Germans’ abilities to move supplies, troops and equipment were seriously degraded. In this atmosphere, care of POWs became a very low priority. I never received any mail and only a few Red Cross food parcels while I was a POW. With our meager diet, I, along with the others, started losing weight. Dysentery had been a problem most of the time after I became a POW - especially after that train ride to this camp. For breakfast we had “tea”. They raked up tree leaves and boiled them for tea. At least it was hot and provided some liquid other than cold water which was available only from a faucet between two barracks that were end to end.. For lunch, there was usually some kind of soup or sauerkraut. I never did like cabbage anyway, but here there was no choice or substitute. For dinner we had some boiled potatoes - sometimes having been frozen and black. Also we got about a 1/8 of a loaf of their black bread, which contained about 1/3 sawdust for filler. Once a week we got a little dab of margarine and a tablespoon full of sugar. There was seldom any meat, but if there was, it was in the soup at noon. Each of us had been given a German knife, fork & spoon.

Razor

Silverware

Swastika on Handles I was given a razor and five blades and they lasted me as long as I was a POW. We learned how to sharpen and re-sharpen them. About once a month one of the POW’s who had a pair of hand clippers gave us haircuts. There were no showers so we had to wash the best we could with the one cold-water faucet when we could - usually after standing in line. The only soap we had came from the Red Cross food parcels. While I was a POW I had no toothbrush or dental care. The only medical help I received was from Dr. McGee before he was transferred to another camp. However, all he could do was suggest simple home remedies with no medications. Our latrine was in a separate building that was also used by most of the other barracks in the camp. Occasionally the Germans brought in a “Honey Wagon” and pumped the pit out, as there was no sewer system Every morning and evening we had to line up for Appel where they counted us. If anyone was not there, we all had to stand there and wait until all were accounted for. Nobody wanted to stand out there in the cold or snow in the morning waiting for someone who had a hard time waking up, so we always made sure everybody was up and out there on time. At night the lights were shut off about 9 o’clock and everybody had to be inside until morning. No radios were permitted, and the only authorized news we had was German news that was posted on the bulletin board by them. When a new group of POWs came, they of course could tell us what was happening in the outside world up until they were captured. However, some of the older POWs had been able to put together a secret radio that could get BBC from London. During the day, with someone guarding, the radio was turned on and the news copied on slips of paper and distributed to each barracks to be read that night. Then after the lights were out, with somebody standing guard to prevent any German from catching us, we listened to “the Bird”. The slips of paper were then destroyed immediately. The Senior American officer, Col. Paul Goode, and his predecessor, Col. Drake - both West Point officers - dealt with the German camp commander, Col. Schneider, to settle any problems that developed between the POWs and the Germans. From the beginning at this camp the senior American officer had set up a typical military staff to run the camp somewhat like any Army unit, with pretty strict discipline for all those in the camp. This prevented the problems of mob rule as happened in some camps and with some nationalities. In the camp we had a library. Some of the books were there previous to the arrival of the first American POWs and others were brought in later by the YMCA representative from Sweden. He also brought in various equipment for athletics, as well as some musical instruments and playing cards. I couldn’t use the library because the Germans had broken my glasses when I was captured. I did spend lots of time playing cards and just visiting. I don’t know how it got there, but there was a pet Raven in our barracks most of the time. It often landed on the table where we were playing cards and would pick one up and fly over to the other side of the room with it. Most of the POWs here were college graduates or had been in college and were from all professions and all parts of the U.S. Some had been college professors before being called for active duty. They, as well as other POWs, taught college level classes on subjects of their expertise. At night the lights were shut off about 9 o’clock and everybody had to be inside until morning. Despite the fact that Oflag 64 was in such a

remote location and there was virtually no chance of an escapee getting

back to Allied lines, a number of escape attempts were made. But the

only successful one I ever heard about involved three POWs who implanted

coal dust under the skin of their chests, and then later put on a

coughing act until the Germans finally took them out to a doctor. X-rays

showed spots on their lungs, and they were diagnosed as having the

incurable disease of Tuberculosis, and were repatriated. A number of

other escape attempts were made, but resulted only in the harassment of

the Germans.

One day in October or November the Germans got everybody out for an extra Appel while they went through all the barracks and took all the parts of uniforms they could find. I had all mine on that I was captured in, so I didn’t lose anything. Later we found out that these uniforms were used by Otto Skorzeney’s SS commandos to impersonate American soldiers in the Battle of the Bulge. Another secret that the Germans suspected, but never could locate, was a tunnel that was dug from one of the barracks to escape through. It extended under the fences and beyond. One of the POWs was a mining engineer and with a lot of ingenuity and help, they had dug down and out through the sandy soil by shoring it up with the bed boards. By taking a few from each of about all the beds in camp, it wasn’t too noticeable as long as our so-called mattresses were held up and we didn’t fall through. Had the Germans missed these “extra” bed boards, we could have been charged with destroying German property, which was a capital offense and punishable by death. Other works of engineering ingenuity resulted in electric lights in the tunnel and an alarm to warn the one digging in the tunnel in time so he could get out and look presentable if a guard came close. Other people disposed of the dirt from the tunnel by scattering it outside over the compound or hiding it in the attic in Red Cross food boxes. In early November winter was coming on and I had gone from about 175 pounds at the time I was captured down to about 140 pounds. In addition to the weight loss, I began to suffer medical problems, which were attributable to a lack of vitamins and other nutrients. I kept getting styes on my eyes and in the latter part of November I caught a cold that settled in my chest and developed into bronchitis and then into pneumonia. I couldn’t even talk for a week or two. I am sure this was a result of the damage to my lungs while at Anzio. I finally got over it about Christmas time.